Professor Kevin Fenton, Regional Director for London, Office for Health Improvement and Disparities

Improving asthma-related outcomes and tackling health inequalities in London must go beyond excellent clinical management and personalised care for children, young people and their families to embrace a population health approach. Understanding and addressing wider factors linked to asthma – including importantly the quality of the air we breathe – is key to this public health approach.

The quality of air that children and young people grow up breathing can affect the likelihood that they will develop asthma and can also trigger asthma attacks. Breathing tobacco or vape smoke[1], other indoor air pollutants in the home environment and outdoor air pollution[2] are all causes of asthma and triggers for asthma attacks. Moreover, we know that exposure to these risk factors is not equally distributed, with children living in our more deprived communities more likely to be exposed to these environmental and behavioural risk factors.

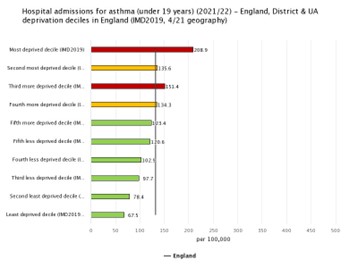

These inequalities in the air we breathe mean that children and young people growing up in London’s most deprived areas are three times more likely to be admitted to hospital with asthma and are more likely to develop persistent asthma (asthma that continues into adulthood).

Tobacco and Vaping

70% of children and young people with asthma in London either smoke or are exposed to secondhand smoke.[3] Smoking inequalities begin before birth. Smoking in pregnancy is five times higher amongst women living in the most deprived areas, and this inequality plays out throughout childhood, with smoking prevalence amongst the most deprived 16–19-year-olds four times higher than those older teenagers living in our most affluent areas[4] While vaping is a relatedly recent phenomenon, early evidence suggests that vaping may increase the likelihood of developing asthma and having an asthma attack.[5]

The Home Environment

Households with children, households with a low income, and people from minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely to live in poor quality housing, which means they are more likely to be exposed to damp and mould.[6] Exposure to a poor-quality home environment in the early years of life increases the chances of developing persistent asthma (asthma that continues into adulthood)[7].

Air Pollution

All children in London are exposed to air pollution. The most recent review of air quality in London found that all schools in London are exposed to levels of air pollution above World Health Organization guidelines. It also showed that deprived communities, and minority ethnic communities are routinely exposed to higher levels of air pollution.[8]

The Future

Continuing our efforts to drive down London’s smoking prevalence, treating tobacco dependence and improving air quality indoors and outdoors are all important elements of a public health approach to improving asthma outcomes and reducing asthma-related inequalities.

There are several reasons for optimism. Children’s exposure to secondhand smoke has greatly reduced over the past twenty years[9]. The government has recently launched a call for evidence to identify opportunities to reduce the number of children accessing and using vape products, and work is underway to tackle illegal and underage vape sales.

Air quality in London has improved significantly in recent years, with the largest improvements amongst the most deprived populations. Air pollution attributable asthma admissions in children were estimated to have reduced by 30% between 2016 and 2019.[10] Indoor air quality, a previously neglected area of research, is receiving increased attention, for example in the CMO’s recent report into air quality.[11]

The range of measures being taken in response to the coroner’s Prevention of Future Deaths report, following the tragic death of Awaab Ishak in Rochdale – such as the amendment to the Social Housing Bill to introduce “Awaab’s law”, requiring landlords to fix reported health hazards within specified timeframes, and the anticipated publication of guidance for the housing sector on the health impacts of damp and mould in homes this summer – should drive improvements in the poor housing conditions to which too many London children are exposed.

There is still a long way to go, however, this year’s #AskAboutAsthma theme of “widening our view” is a timely reminder of the importance of taking a population health approach and the continuing need to work together across organisations and sectors to address important environmental and behavioural determinants of asthma outcomes and inequalities.

Visit the 2023 #AskAboutAsthma webpage for more blogs, videos and podcasts about asthma care for children and young people.

[1] Martin J, Townshend J, Brodlie M, Diagnosis and management of asthma in children, BMJ Paediatrics Open 2022;6:e001277. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001277

[2] Impacts of air pollution across the life course – evidence highlight note (london.gov.uk)

[3] Quality and Outcomes Framework 2021-22: The percentage of patients with asthma on the register aged 19 years or under, in whom there is a record of either personal smoking status or exposure to secondhand smoke in the preceding 12 months.

[4] ASH-Briefing_Health-Inequalities.pdf

[5] Cardiopulmonary Consequences of Vaping in Adolescents: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | Circulation Research (ahajournals.org)

[6] CBP-9696.pdf (parliament.uk)

[7] Disadvantage in early-life and persistent asthma in adolescents: a UK cohort study (bmj.com)

[8] Air quality exposure and inequalities study – part one – London analysis.pdf

[9] Children’s exposure to second-hand smoke 10 years on from smoke-free legislation in England: Cotinine data from the Health Survey for England 1998-2018 – The Lancet Regional Health – Europe

[10] hia_asthma_air_pollution_in_london.pdf

[11] Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2022 (publishing.service.gov.uk)