Dr Lin Graham-Ray, Visiting Clinical Lecturer in the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, and some very articulate children

“It’s a bit smudgy and funny and it feels like you’ve got prickly plants in your high tummy bit, then your breath gets heavy and tight like a wheezy balloon with no air let in.”

This was the first answer I got from a six-year-old when I asked what it is like to have asthma. It was shortly followed by:

“It’s scary like the same as a monster under your bed scary.”

Working with the voice of the child and undertaking co-production with young people felt a bit the same to me!

However, over the course of the work, some important messages from children were gained which led to new insights and ways of thinking about their lived experiences. Collaborating with them and undertaking a range of activities led to them producing their own asks and wish-lists for professionals. Some were more achievable than others! Here is some insight into what happened.

The importance of co-production

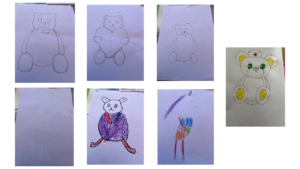

Picture a nurse seconded to a transformation post, armed with some art materials, lots of paper and goodwill, asking 6–11-year-olds what is it like to have asthma. Then find yourself planting flowers, helping with a wormery (not so much fun if you do not like worms) and drawing teddy bears, lots of fun and laughter, but also some time and space to really hear what children were saying. So, what did I understand from this?

Most of the children carried some level of stigma and shame about their asthma, thinking and feeling it was their fault and feeling ashamed when they had to ask for their inhaler in school. When I explored this with them, it transpired that some of it stemmed from the fact that their inhalers were taken and kept somewhere else, usually in a box, so they felt they had no ownership of their device and it had to be “asked for.” Swimming was a particular concern as all the inhalers were put in a box and the child’s name was called out; this felt embarrassing and raised the children’s anxiety.

They were also anxious for their peers who saw them having an exacerbation- they worried their friends were worried and that they might have bad dreams, that they might catch asthma from the car fumes outside. They also worried a lot about global warming, and we spent more time than I expected talking about climate change and David Attenborough – this led to the wormery! (Thanks Sir David!)

Then the challenging work really started. How could we (health professionals) help with some of the anxieties and worries the children had? The answer was a teddy bear.

“Please bring it as a mascot, talk about how the teddy might feel if they had asthma, the teddy goes to school and feels wheezy but it’s ok, as he has friends.”

This progressed to, “Can we have an asthma teddy to keep our inhalers in, so we do not feel different? Inhalers are ugly and even if you put stickers on, it is still an inhaler just with stickers and they look tatty after a while and when you are eight you do not really want stickers any more.”

Building rapport and reducing stigma

I asked if you would still want a teddy then if you are eight and stood back as the answers came thick and fast: “You are never too old for a teddy bear, it’s an ageless thing and it’s not embarrassing and doesn’t feel different and, even if it was, you could say it was someone else’s or you are looking after it, it doesn’t look like an inhaler or something that says you have asthma.”

I accepted this position, being slightly overwhelmed by their valid points. The children were also clear that the bear had to be gender-neutral and a neutral colour. Drawings were produced of a teddy with space for an inhaler. The idea was that the bear could be used to talk about asthma and if anyone wanted to help adults understand, then the teddy could help break down difficult things to talk about.

I accepted this position, being slightly overwhelmed by their valid points. The children were also clear that the bear had to be gender-neutral and a neutral colour. Drawings were produced of a teddy with space for an inhaler. The idea was that the bear could be used to talk about asthma and if anyone wanted to help adults understand, then the teddy could help break down difficult things to talk about.

We tried this out at a teddy bears picnic. I wasn’t asked if I was the nurse who was here to talk about asthma, instead I was asked if that was my teddy, whether it could it stay here, did it have a name… and soon we were having a full-on engaging talk about asthma, but in a way the children found easy and not “Doctorly”.

Some of the work continues and the children’s wish for a bear is being considered, though not the latest model (that had an air quality monitor in its nose , a mould detector in one eye, a secret compartment for sweets, the ability to talk and do your reading homework and a secret spy cam because you never know when you might need one!).

Messages for health professionals from this work include: always talk about asthma to children with asthma but talk to the child about being a child first and if you have a teddy bear to help you explain, all the better.

Watch out for the next blog from South West bear, coming to South West London soon…

You can also watch Lin’s video version of this blog here.

Visit the 2023 #AskAboutAsthma webpage for more blogs, videos and podcasts about asthma care for children and young people.