Neurodiversity is an afterthought at the moment

“Neurodiversity is an afterthought at the moment”: results from a pan-London survey of frontline staff’s views about working with autistic people experiencing homelessness

Autism and homelessness report about practitioner confidence, system barriers and training needs

September 2024 – Scarlett Wright and David Bryceland

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the practitioners who have taken their time to complete this survey alongside doing already challenging roles – your passion and willingness to come together to drive forward systemic change is what makes the homelessness sphere so wonderful to be part of.

We are grateful to our funders and colleagues at MHCLG and OHID London whose funding and support has made this report possible. We would like to thank the colleagues from various organisations who gave their time for our initial scoping meetings, which were integral in shaping the development of this project.

Executive summary

This report explores the views of 186 practitioners working with people experiencing homelessness in London on the topic of autism and homelessness. The report aims to capture

self-reported perceptions of confidence in working with autistic people experiencing homelessness, gaps in training needs, the adequacy of provision for this client group, and suggested systemic changes.

Recent research suggests that 12.3% of people experiencing homelessness are autistic (Churchard et al., 2018), compared with 1-2% of the general population (Brugha et al., 2012). However, practitioners responding to this survey suggest there is a lack of awareness about autism, and a lack of practice informed by autism within services working with people experiencing homelessness, which participants propose creates barriers in accessing appropriate support.

Provided within this report is detailed qualitative feedback which explores participant experiences and viewpoints – focusing on what affects their confidence levels, the changes they suggest should be made to training and resources, and what changes can be made within the system, specifically focusing on homelessness services. Suggested changes to training and resources can be found on page 45 and suggested systemic changes can be found on page 69 these accounts can be utilised by system leaders and managers to inform the development of systems and services. This survey seeks to catalyse support for systemic change and raise awareness of the experience of autism and homelessness.

Key findings and information

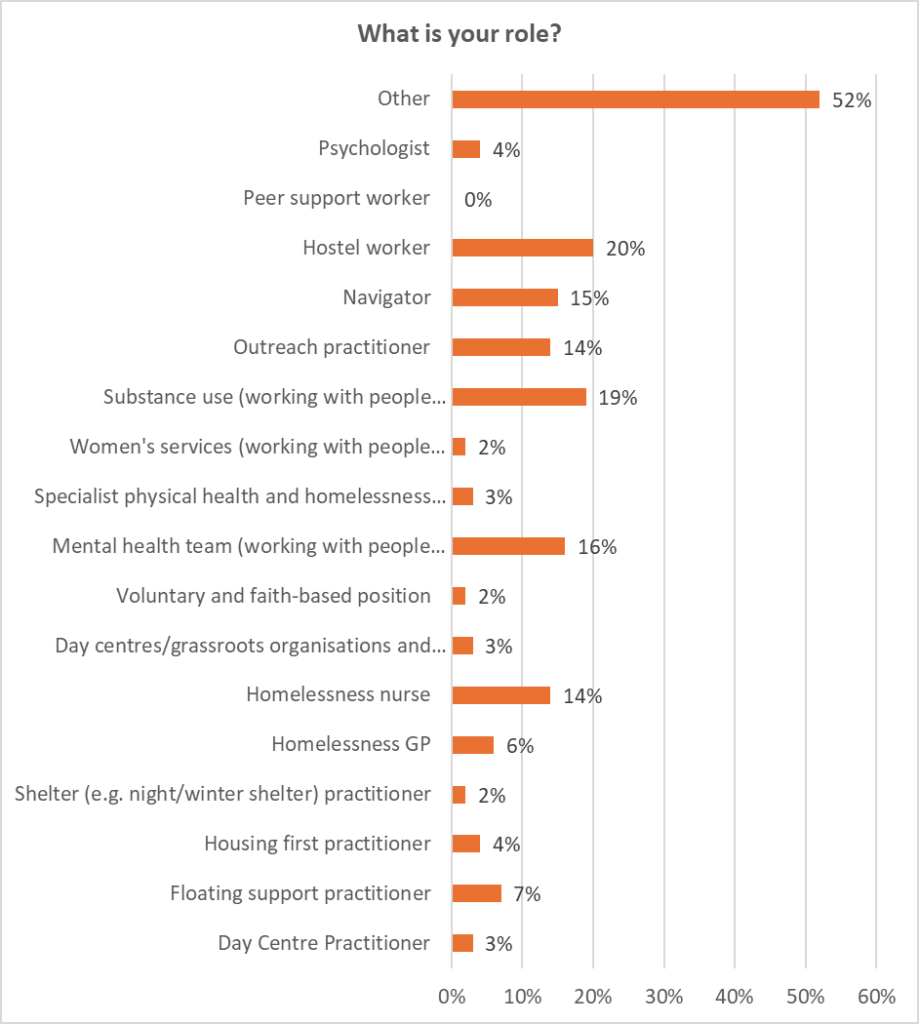

- The survey was completed by a wide range of professionals, with the highest percentage of participants being hostel workers, substance use practitioners and practitioners from specialist homelessness mental health teams.

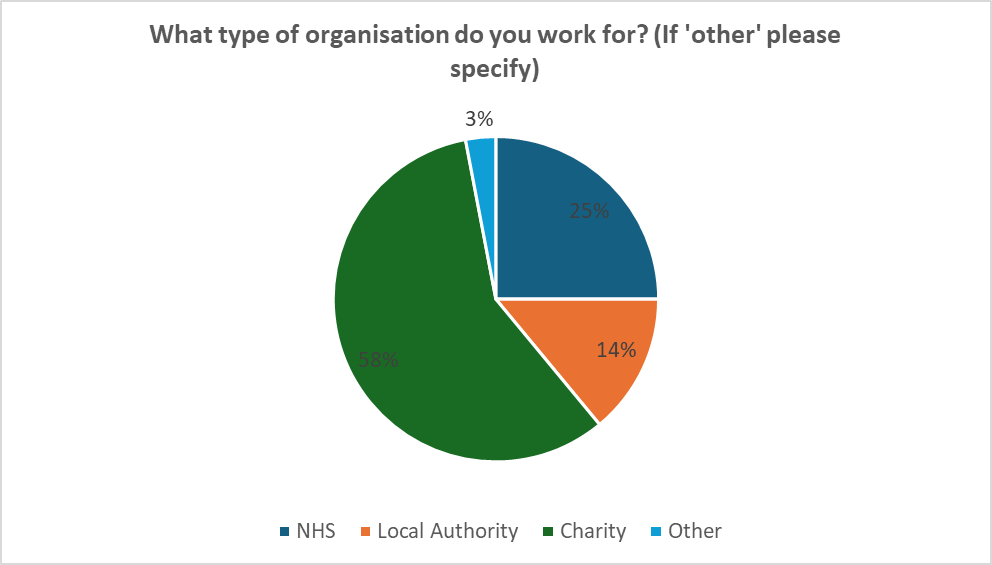

- 58% of participants work within the charity/third sector, with the second most prevalent group working within the NHS (25%).

- The majority of participants self-reported that they would feel confident recognising autistic traits (68%), speaking with clients about autism (71%) and supporting those with additional needs (58%) – however, most participants self-reported that they felt unconfident in their knowledge and understanding of local autism services (45%).

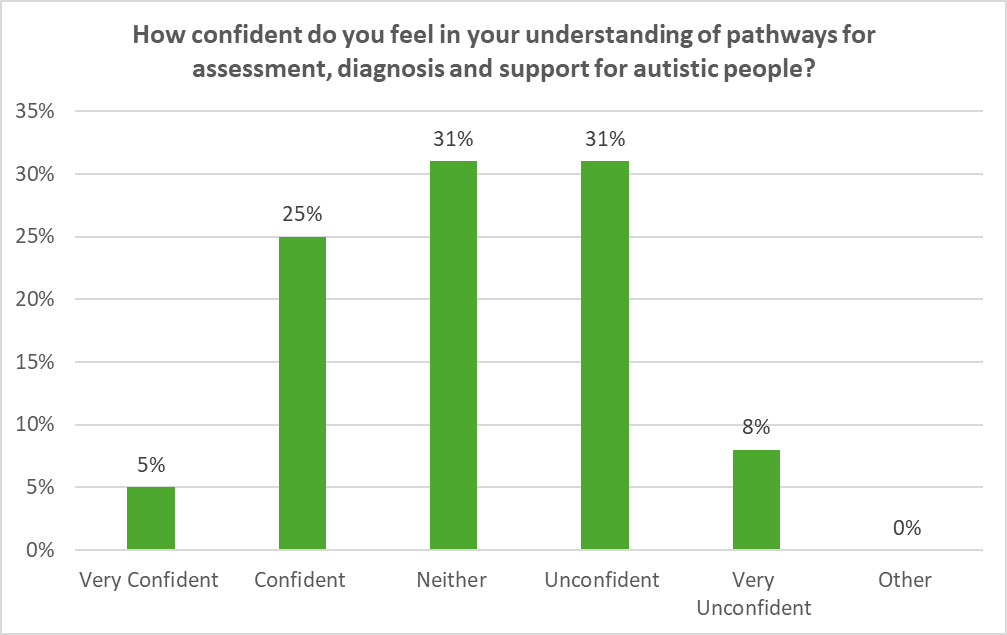

- 39% of participants self-reported feeling confident in their understanding of pathways for assessment, diagnosis and support for autistic people, compared with 30% of participants reported that they did not feel confident about this topic – suggesting a significant split between participants.

- The key drivers of confidence levels included practitioners having lived experience themselves, the availability of knowledge about autism services and physical environments making it more challenging to support autistic people. Further factors affecting confidence includes access to specialist services and practitioners with extensive experience, the lack of awareness about autism within services, lack of adequate training and resources, and struggling to know whether someone is autistic or struggling with another co-occurring need such as substance use.

- 42% of participants felt that their organisation’s training or resources do not adequately equip them to work with autistic people experiencing homelessness, compared with 26% who do believe their organisation’s training successfully equips them. The authors highlight that this may be due to autism training being more accessible and a more mandatory component of NHS training.

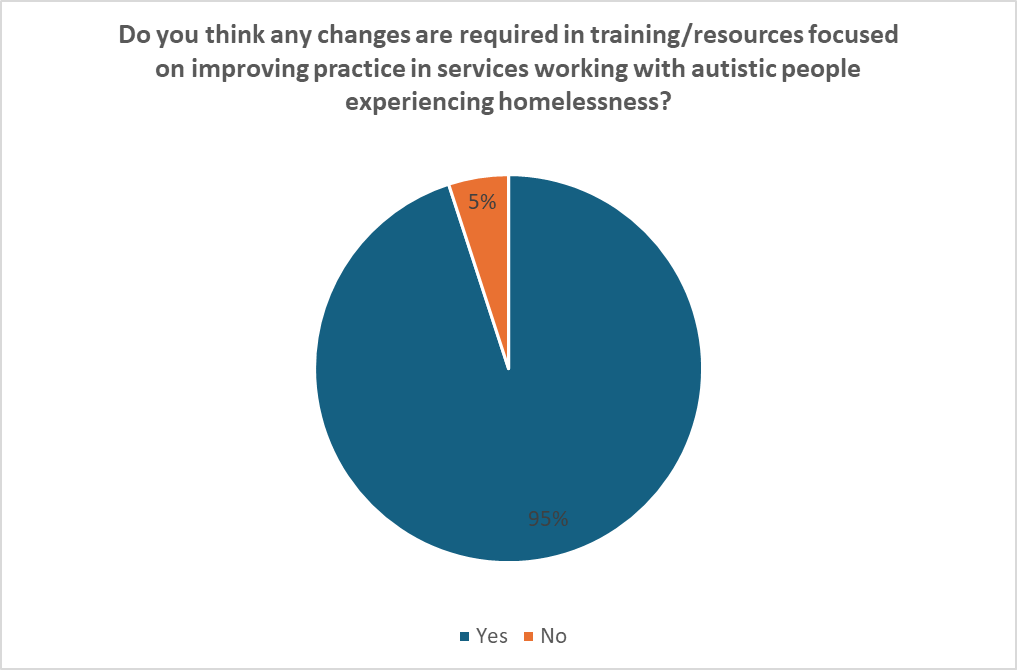

- 95% of participants felt that change is needed to improve training and resources for services working with autistic people experiencing homelessness. Details of the changes that participants would want to see can be found in the proposed changes to training and resources section.

- Training and awareness around autism needs to factor in understanding of the spiky profile of autism and promote nuance rather than stereotyping.

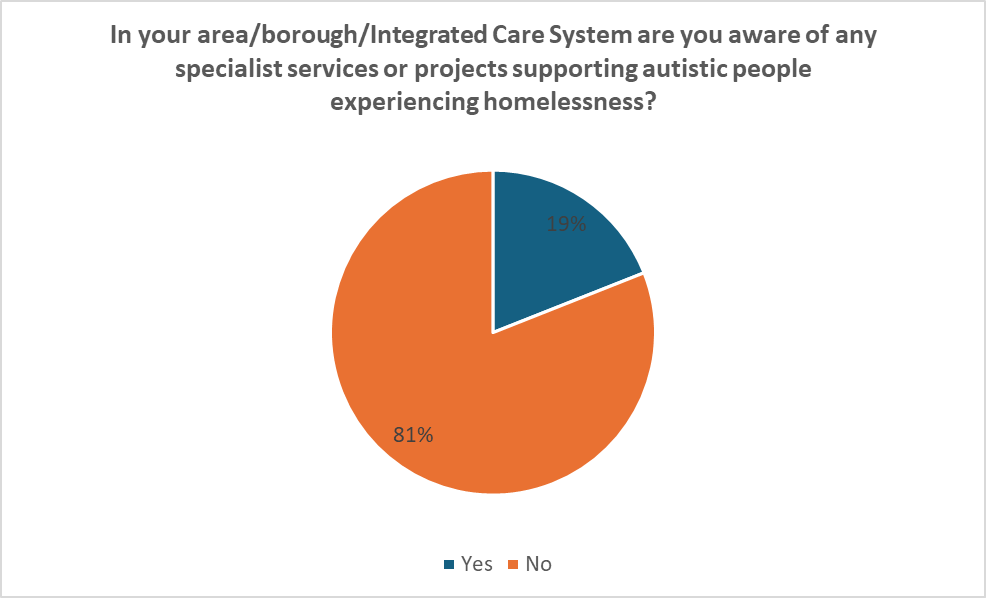

- 81% of participants were not aware of any specialist services in their area that would work with autistic people experiencing homelessness.

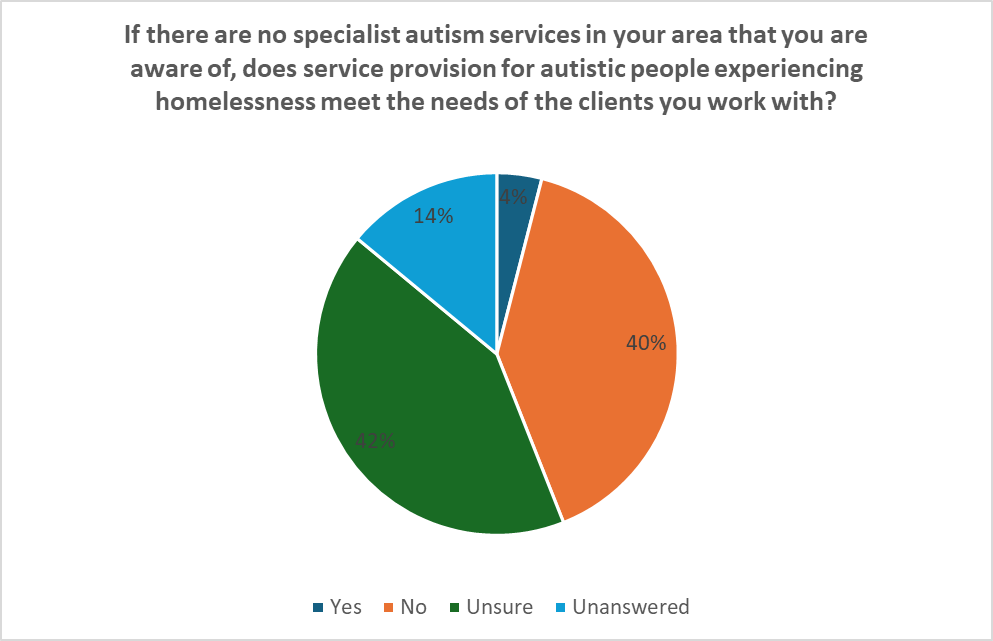

- 14% of all participants reported that they believe mainstream services in their area meet the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness. Details on why this is felt to be the case are explored in the mainstream/non-specialist autism services section.

Key recommendations

This survey focused on capturing the views of participants, and while many recommendations have been made about changes that could be made within the system, the authors acknowledge that homelessness systems are faced with significant levels of demand and pressure. These recommendations seek to act as a guide and to represent the views of participants, however, due to the online modality of the survey, how these changes could be implemented could not be explored in detail in this particular report.

The key recommendations, based on the accounts of the survey’s participants, are as follows:

- Greater recognition and awareness of the prevalence, presentation and support needs for autistic people (and for those experiencing co-occurring autism and homelessness), coupled with nuanced understanding of the spiky profile of needs and presentations.

- Flexibility and accommodation of autism within services, both in the environment and in interactions with practitioners.

- Co-producing change with autistic people.

- Embedding gender-informed approaches and increased understanding of women’s experiences of autism and homelessness.

- A need for commissioners and funders to better understand the needs of autistic people, thereby improving the identification of and commissioning for appropriate outcomes.

- Structural changes to pathways for support, including access to rapid and flexible diagnostic assessments, specialist open-ended support and resources, preventative support, amendments to priority need and statutory duties, and appropriate accommodation and pathways.

- A joined-up approach throughout the system – joint working and sharing information between services, and pooled funding.

- Recurrent in-person training for all staff about autism and homelessness.

The authors would like to conclude by recognising the overwhelming amount of support from across the system for this work – from frontline staff to commissioners, from third sector to NHS colleagues.

There was a huge amount of enthusiasm for change, and participants expressed gratitude at being able to share their thoughts, and for this issue being brought to the fore. The authors hope that this report catalyses support for systemic change around autism and homelessness and provides an exciting opportunity to work together to improve the systems we work within.

Introduction

The following report was produced by colleagues from Transformation Partners in Health and Care’s (TPHC, formerly Healthy London Partnership) Co-Occurring Conditions Programme. The London Co-occurring Conditions Programme works alongside London partners to ensure that there is no “wrong door” for the population who are experiencing homelessness, who have co-occurring substance use, mental health conditions, learning disabilities, or autism. The programme has been funded since 2022 by the Rough Sleeping Drug and Alcohol Treatment Grant overseen by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) to improve the way the health system and services work for people experiencing homelessness.

This report seeks to help practitioners, commissioners and funders to understand the pan-London perspectives of frontline workers, working with the aforementioned client group, around working with autistic people experiencing homelessness and the system around the client.

Existing literature and research

Autism refers to a neurodevelopmental condition that is experienced throughout life and can include traits such as sensory sensitivity, repetitive routines and behaviours, focused interests, and differences in social communication (NICE, 2021).

The Autism and Homelessness Toolkit explains the autistic spectrum and the misconceptions that one person can be “more autistic” than another. However, this is instead viewed as a spiky profile which “attempts to illustrate that each autistic person has unique strengths and also unique challenges…for example, an autistic person could have strengths in their attention to detail…the same autistic person could however struggle with traditional verbal communication” (HomelessLink, 2024, p.6).

Homelessness can refer to sleeping on the street, lacking a secure place to live, sofa surfing, and living in hostels or refuges (Amore et al., 2013).

Current research suggests that 12.3% of people experiencing homelessness are autistic (Churchard et al., 2018), compared with 1-2% of the general population (Brugha et al., 2012).

Churchard and colleagues completed preliminary empirical research into the prevalence of autistic people within groups of those experiencing homelessness, based on a sample size of 106 people working with UK-based street outreach team. Stone’s (2019) work around why autistic people are more prevalent in groups experiencing homelessness suggested that factors may include “social vulnerability, unemployment, and difficulty interacting with services.” However, it is also noted that:

“Homelessness is not an outcome of autism, but of the disabling barriers autistic adults face throughout their lives” (Stone, 2019, p.1).

A further study conducted by Stone et al., (2023) sought to capture the experiences of homelessness for autistic people, and how to best support them through narrative enquiry. Key findings included accounts of participants recalling being turned away from support for not meeting thresholds, which was believed to be due to support workers’ lack of knowledge around autism.

Systemic challenges clients experienced includes environments in hostels, with some participants preferring to stay on the street due to the distress caused by these environments. Key recommendations from Stone et al., (2022)’s research included increasing awareness of autism within frontline services, to eliminate systemic barriers to accessing support for autistic people, and to have an increased focus on autism within homelessness practice and policy. Further research conducted by Lockwood Estrin et al., (2022) sought to identifying gaps in knowledge and practice, and suggested research development around autistic women’s experiences of homelessness.

Key suggestions included exploring the differences in women’s experiences of homelessness in relation to gender-based violence and domestic abuse and improving awareness of autistic women’s experiences within services.

The authors are not aware of any investigation into the views of the workforce around autism and homelessness.

Aims

This report aims to capture the views of frontline staff working with people experiencing homelessness in London. The results have been shared at a launch event aimed at influencing systemic change, highlighting key recommendations with commissioners and system leaders from across London.

The survey that participants completed aimed to understand the following:

1. How do frontline staff supporting autistic people experiencing homelessness self-report their confidence levels in working with this client group? What are the drivers of this confidence level?

2. To what extent do frontline staff supporting autistic people experiencing homelessness believe that this client group’s needs are being met?

3. What gaps in system provision are perceived by frontline staff supporting autistic people experiencing homelessness?

Based on the findings of previous literature highlighting an increased prevalence of autistic people experiencing homelessness, this project sought to raise awareness of autism as an issue to be aware of when working in homelessness settings. Further, the project aimed to identify systemic gaps in pathways of support, training needs and levels of confidence, based on accounts from frontline staff working with autistic people experiencing homelessness. The findings of this report were shared at an online event in September 2024, which invited substance use, rough sleeping and supported accommodation commissioners, alongside specialist practitioners. The event was attended by 62 commissioners and strategic leaders from across London, and catalysed support for systemic change in this area. Further details of the learning from this event are detailed in Chapter 4 of this report.

The authors hope that this survey aids commissioners, managers and practitioners in understanding the current workforce’s views, and potential points of actions that can be taken to improve provision for clients and staff alike.

Methods

Following several months of scoping meetings with specialist professionals, managers and commissioners from homelessness and autism services in London around the topic of autism and homelessness, research questions were planned and a survey was developed. The questions within the survey are detailed in the report findings. The online survey was anonymous and required participants to give informed consent. Participant recruitment involved sending the survey to the team’s existing professional networks via email, and the uptake snowballed from the original advertisement of the survey.

The email sent to participants specified that they must work in a service in London supporting adults experiencing homelessness, and that a range of practitioners could submit a response – whether they worked in Housing First, outreach, hostels, peer support, or specialist GPs, voluntary and faith groups and day centres, as examples. The emphasis in the email was around supporting adults experiencing homelessness in any capacity, whether the potential participant had worked with someone who identifies as autistic or has a diagnosis, or not. The qualitative data within the survey was thematically analysed following Braun and Clarke’s (2013) guidance.

Any details pertaining to specific boroughs or organisations were anonymised to focus the data on themes, as opposed to specific feedback about particular services. Descriptive statistics are provided for the quantitative data and presented in graphs. 186 practitioners participated in the survey.

Findings

The following sections detail the qualitative and quantitative responses from participants. Some questions were answered by all participants, while others were self-selecting, meaning that participants only answered if the question applies to them. All quantitative data displayed in the graphs below are calculated and displayed as percentages.

Participant details

The following graphs give details of participants’ roles, number of years of experience within the sector, and whether they have worked with autistic people, among other information.

Participants responding to the survey were asked to give details of their role/job title. As highlighted in Figure 1, a wide range of professionals participated in the survey, and the most prevalent groups were hostel workers, substance use workers and practitioners from specialist homelessness mental health teams.

Figure 1: Participant roles and job titles

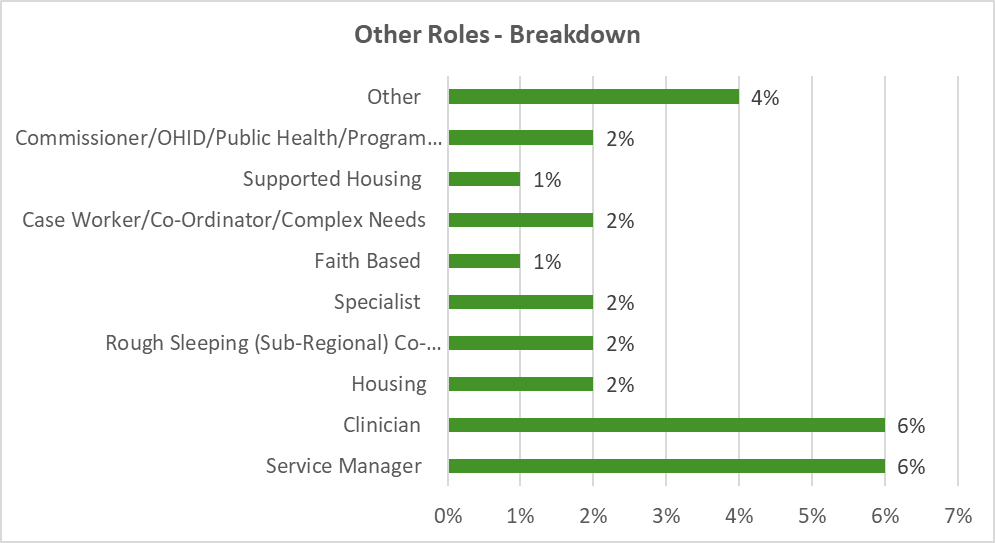

Figure 2: Breakdown of “other” roles and job titles

Breakdown of roles where participants reported they were a ‘Clinician’:

- Speech and Language Therapist

- Social Worker/AMHP-Homelessness CMHT

- Psychoanalytic Psychotherapist

- Psychotherapist

- Social worker (Autism Lead)

- Social worker in integrated street population team

- Counsellor

- Occupational therapist

- Consultant psychiatrist specialising in homeless health

- Adult nurse

Figure 3: Type of organisation participants’ work for

Figure 3 highlights that 58% of participants work in the charity/third sector, with the second most prevalent group working within the NHS.

“Other” organisations breakdown –

- Housing Association

- Faith GroupAs highlighted in Figure 1,

- DHSC

- Employed by homeless charity, working in NHS Mental Health trus 58% of participants work in the charity/third sector, with the second most prevalent group working within the NHS

- Hospital Homeless Team

*21.5% of the total number of participants did not answer this question – it was the only question that was added to the survey after it had been launched.

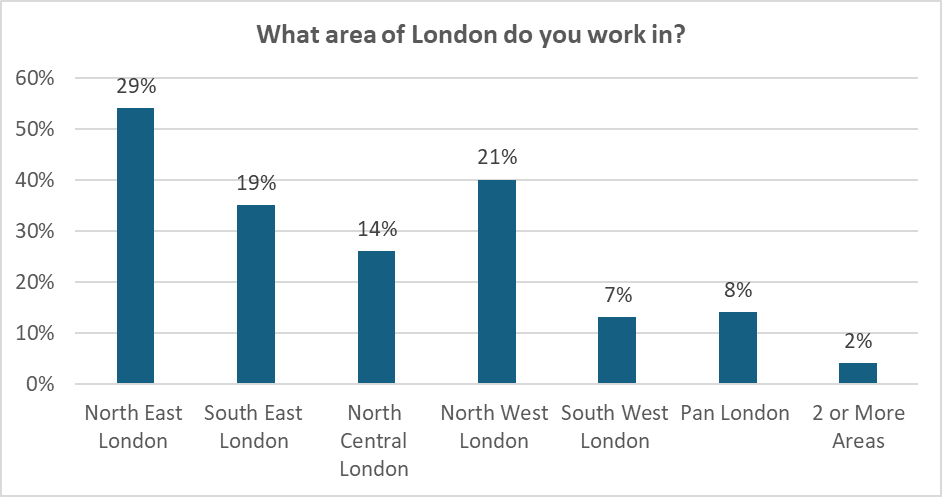

Figure 4: Area of London that participants work in

Figure 4 highlights that those working in Northeast London accounted for most responses (54%).

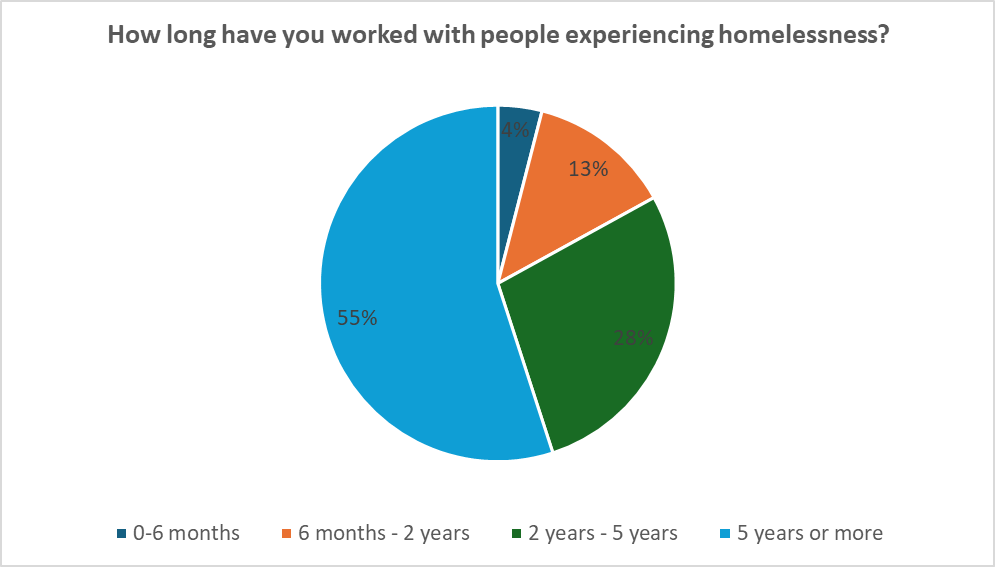

Figure 5: Length of time that participants have worked with people experiencing homelessness

Figure 5 illustrates that 55% of participants have been working with people experiencing homelessness for over five years.

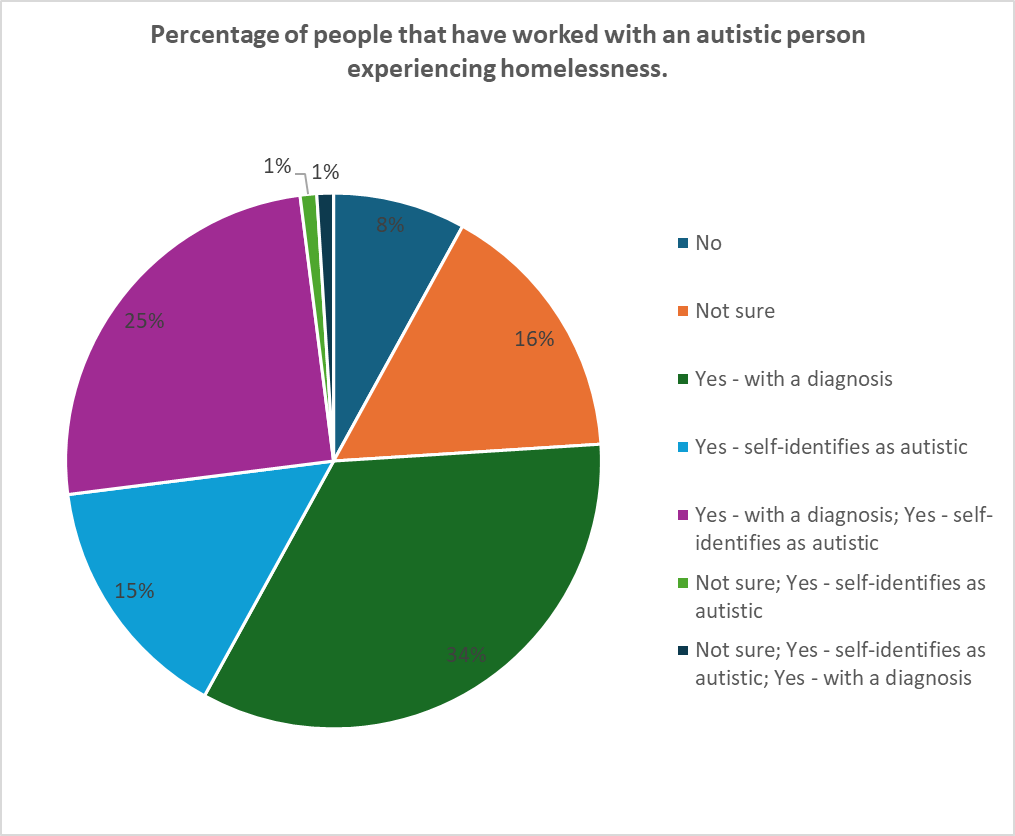

Figure 6: Percentage of participants who have worked with an autistic person experiencing homelessness

With reference to Figure 6, this question allowed participants to tick multiple boxes – meaning that some participants selected that they had worked with clients with a diagnosis, and those who self-identify as autistic (25%), while 8% of participants said they had not worked with autistic people at all.

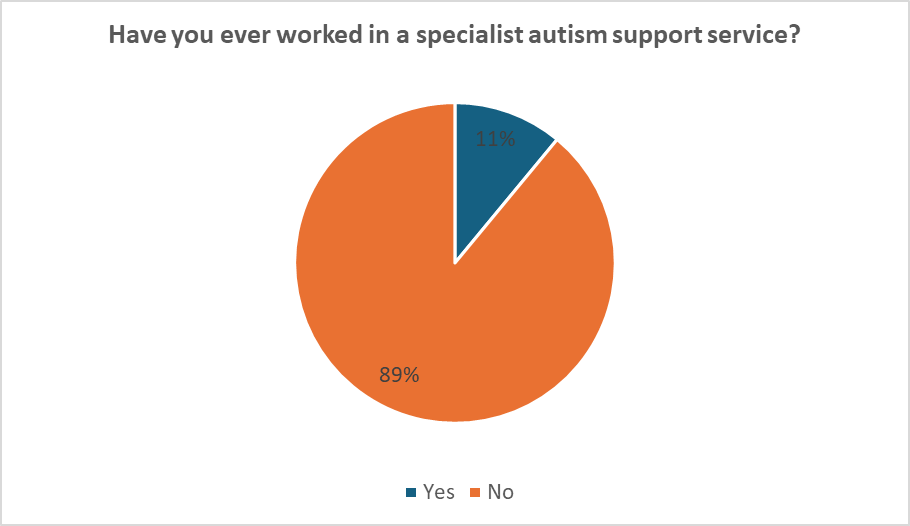

Figure 7: Percentage of participants that have worked in a specialist autism service

As highlighted in Figure 7, most participants (89%) had not worked in a specialist autism service, but 11% of participants have worked in specialist autism services.

Confidence of practitioners working with autistic people experiencing homelessness

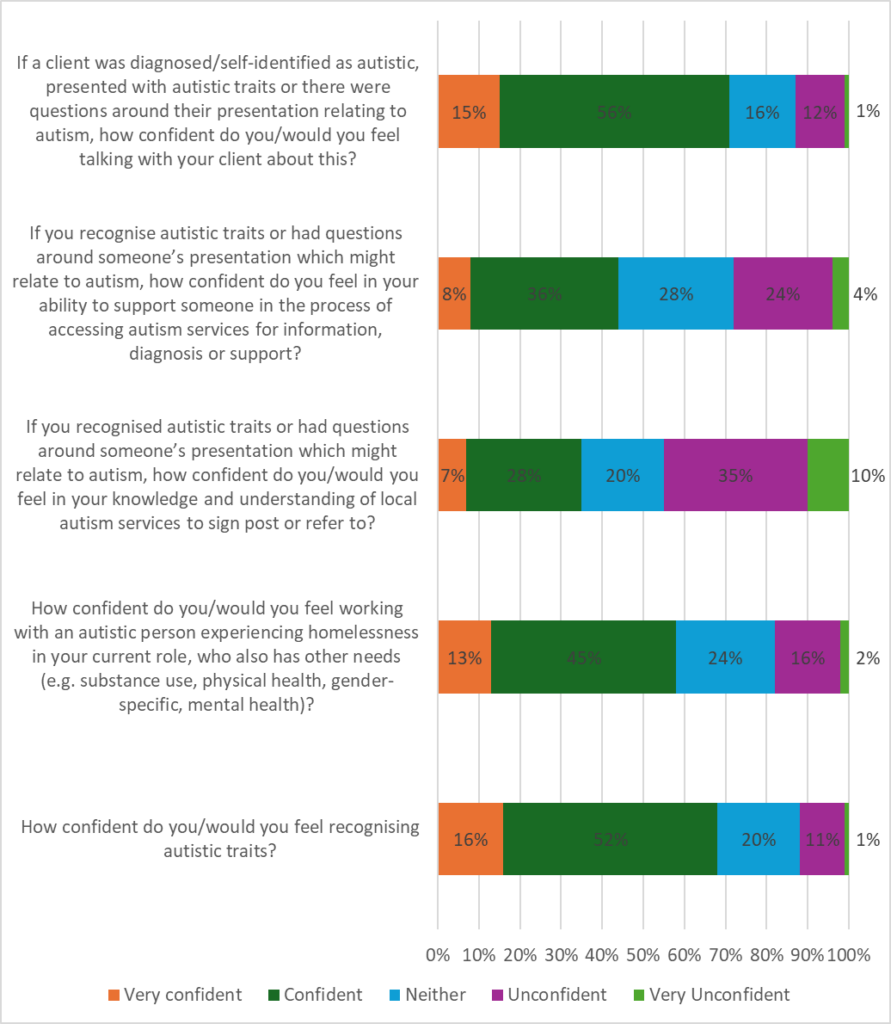

The following section explores participant confidence levels when working with autistic people experiencing homelessness, through self-reported likert scales, and qualitative explanations. From the first quantitative question, the majority of participants self-reported feeling confident in recognising autistic traits, talking with clients about autism and supporting those additional needs (Figure 8). However, most felt unconfident in their knowledge and understanding of local autism services (45% of participants).

Figure 8: Participant self-report of confidence levels on a Likert scale in response to situational statements

Figure 9: Self-reported confidence of participants’ understanding about pathways for assessment, diagnosis and support for autistic people

Figure 9 highlights that 39% of participants self-reported that they do not feel confident in their understanding of pathways, whereas 30% of participants suggested they did feel confident.

The first qualitative question asked participants to explain why they had rated the above likert scales – referring to confidence in recognising autistic traits, supporting autistic people and speaking to clients/patients about being autistic.

The following key themes affecting practitioner confidence were identified:

- Confidence underpinned by lived experience (from self or others)

- Knowledge about autism services and how to refer

- Physical environments make it more challenging to support autistic people

- Systemic barriers and lack of service provision

- Extensive professional experience, academic knowledge, and working within specialist provision – plus colleagues with these experiences are a valued resource for others

- Lack of training, resources and knowledge about autism

- Co-occurring needs (substance use, homelessness, mental health) alongside autism

- There is a lack of awareness about autism within services

- Clients not having a formal diagnosis – not wanting to overstep or misdiagnose, and stigma around autism

Confidence underpinned by lived experience (from self or others)

A core theme throughout the data for this question was that participants felt more confident working with autistic people because they themselves are autistic, they have a friend, colleague or family member who is autistic, or they have done their own research outside of work.

One participant noted:

Mainly due to a relative with autism, I have researched thoroughly. When I come in contact with autistic clients where I now work, I was comfortable with the situation, and able to ask relevant questions to other staff, and feel confident in directing client to other professional services. Had I not had a family member with autism, I would be much less confident.

The responses here may suggest that formal training for many professionals does not feel sufficient, and that exposure to people with lived experience of autism is important for bolstering staff confidence.

Knowledge about autism service, diagnosis, pathways, and how to refer

Many responses noted a lack of knowledge and understanding of where to go for support for autistic clients. This included not knowing how to refer patients, how to access support, or what specialist services area available in their area.

Participants also noted that this was compounded by clients with co-occurring needs such as homelessness or substance use and feeling that they did not know which services would be able to work with higher levels of need and worrying about referrals being rejected. The level of confidence differed greatly between participants.

I would feel confident supporting a client to begin the assessment process, but not know where to access support or resources in the interim

Whereas another noted:

I feel confident about supporting a person with autistic traits, less confident in knowing where and how to get support from statutory or clinical partners.

In one borough this theme confidence was said to be higher due to greater awareness, events and directories of services – highlighting that staff confidence is boosted by knowledge and understanding of local systems and services, and how to access them.

Physical environments make it more challenging to support autistic people

Participants described service settings (including hospitals and hostels) as “sensory overload” and this was explained through a lack of resources.

Not even one accommodation service in my organisation has the financial means to provide an appropriate physical environment for autistic clients or to train all staff.

While there was a lack of detail in this specific question around what participants meant by the difficulties created by the physical environment, it is important to note that this factor detrimentally affected staff confidence in working with autistic people. Further research could consider how and why these environments mitigate staff confidence.

Systemic barriers and lack of service provision

A strong theme within the data centred on system barriers and lack of service provision in varying areas affecting participant’s confidence levels. For example, one participant’s comments highlighted the thoughts echoed by many others.

I would feel confident supporting a client to begin the assessment process but would not know where to access support or resources in the interim. It can also be challenging to support someone through this process when wait times are lengthy for assessments and move-ons happen regularly. Needs are also often overlooked and deemed to be as a result of substance use or chaotic lifestyles. Services are also not set up to support or meet the needs of people who are autistic, and autistic clients might be deemed as ‘difficult to work with’ or ‘non-engaging’ before a diagnosis or adaptions are even considered.

As illustrated here, participants alluded to the idea that the system is challenging to navigate for practitioners, let alone with and for clients. The systemic barriers that participants also cited included long waiting lists, referrals being rejected due to co-occurring needs, lack of post diagnostic support, and a lack of access to autism/specialist services.

A further critique of the system affecting staff confidence highlighted the lack of prioritisation of autism.

Often where autism is an underlying support need, I think it can be considered as not a priority by services in comparison to substance use or mental health problems even though they could be linked.

It seems that not only is autism not attended to within the homelessness system in some services, but practitioners feel their confidence is affected by these cultural aspects when their professional expertise is undermined.

I am not sure about how to refer and when I have raised the issue of autism or ADHD being a possible factor in cases e.g. at MDTs or ward rounds I have felt it goes unheard or is dismissed and I am told there are very long waiting lists for assessment and that a person needs to be stable in other areas.

These accounts may suggest that the systemic barriers themselves, such as long waiting lists, can inhibit practitioners’ confidence in exploring whether this is present in a client’s case, and whether culturally the teams around them support this too.

Gender-informed work

Another key theme that was mentioned by a minority of participants, but is an important thread, is gender-informed autism work. One participant explained:

I am not confident in knowing about local autism services and less confident that they would be able to work with women with coexisting needs like homelessness and sex working, which is the area I work in.

It appears that practitioner confidence may be influenced by the perceived competence of the local system to work with the client group they are engaging with.

Extensive professional experience, academic knowledge, and working within specialist provision – plus colleagues with these experiences are a valued resource for others

A clear mitigating factor suggested by participants was professional experience, knowledge, working in multi-disciplinary teams, and being a specialist professional, and for participants that do not have the aforementioned experiences, they felt that having access to colleagues with this knowledge and experience improved their confidence.

Participants noted that where these experiences and expertise were lacking, either in their professional experiences and training or in the teams they work with, this affected their confidence detrimentally.

I am fortunate to have many years of experience working with people with autism previously to working in the homeless sector. I believe this is the only reason I feel competent at working with homeless individuals with autism.

I cannot remember being offered any training in relation to supporting people with autism since working in this sector and often find myself using my own previous experience to support colleagues who may be working with people with autism.

I work in [a borough] where we have access to [a specialist service] for homeless people who experience communication challenges. We also have an onsite psychology, neuropsychology team and occupational therapist in our pathway who can support with formulations and learning.

In my borough there used to be a specialist worker who was able to assess and diagnose autism, but this role no longer exists. I am now unclear as to how to access specialist workers except by going through a GP, but I am aware this is a lengthy process and due to rough sleepers frequently missing appointments or often being hard to engage with it would make it even more difficult to access these services.

My team are extremely knowledgeable, and they are a multi-disciplinary team so they would support me to address these questions.

There seemed to be a split in the narratives between participants who had formal clinical training in the NHS (GPs and Speech and Language Therapists) and those who were in non-NHS homelessness roles – those without clinical training seemed to suggest a lack of training and specialist expertise, which was at times mitigated by extensive experience with the client group, or access to colleagues with specialist training or extensive experience.

Lack of training and knowledge about autism

A core theme that participants identified that affected their confidence was training and knowledge about autism itself. This was identified more widely in non-NHS settings, where participants suggested that there is a lack of training about autism, and that they would struggle to understand the intersecting presentations of autism, homelessness, substance use and mental health. Participants suggested that training helps to highlight gaps in knowledge, helps them to understand how to have conversations with someone who may be autistic, and to understand how to refer and support autistic people.

Autism awareness has not been a feature of services I have worked in, and I am embarrassed to say that I have not prioritised this as an area of self-learning to look into (until now). I have almost no knowledge about autism or how to work with those who are or may be autistic. I have never worked with a client known to have autism.

I have attended autism awareness training in the past but could definitely do with a refresher. I also think my knowledge and awareness of autism is limited to people who have very obvious or “stereotypical” traits.

I think I have probably worked with a lot of people with autism, but they are either undiagnosed or I have not spotted it. Working with people with Autism or training around this has never been a core training.

I think the above highlighted identification process/signposting for Autism is very much part of my work as a GP.

A small minority of participants mentioned the Autism and Homelessness Toolkit which suggested that it improved participant confidence, however, the reasons why were not explored in detail.

Co-occurring needs (substance use, homelessness, mental health) alongside autism

Participants suggested that clients experiencing homelessness also present with co-occurring needs, such as substance use and mental health difficulties, and this was seen as a greater challenging as participants were unsure whether clients’ behaviour is due to autism, or those needs.

I wouldn’t really know how to approach someone who doesn’t self-diagnose as autistic but who I believe does have traits. Particularly as the spectrum is so large and when compounded with other needs it would become more difficult to determine where those traits come from, and the impact of substance use on daily interactions with an autistic person.

As mentioned by this participant, not knowing why certain behaviours are occurring undermines the confidence of practitioners to engage in conversations with clients about autism, or in knowing how to support them. This issue is complicated by the spiky profile and autism spectrum referring to the varying ways that autism can present:

I am aware that autistic traits vary a lot from person to person and can overlap with other conditions, so I wouldn’t feel confident to say someone definitely had autistic traits.

Other participants suggested that co-occurring needs could mask autistic traits, making it more challenging to identify someone’s needs, and this also affected their confidence in working with potentially autistic people.

Due to the often multiple needs of people experiencing homeless, including needs such as substance use and/or mental health, in addition to often chaotic lives, Autism can be masked and more difficult to identify.

This issue seems to be compounded by participants not knowing whether a patient/client has been diagnosed as autistic, and not wanting to assume or overstep.

I would be confident discussing but hesitant not to overstep my role and affirm potential false beliefs, so I want to know how to signpost to the correct services.

I think challenging anyone’s perceptions of how they identify would be difficult, and not being in their shoes, I am not sure we are qualified to challenge this.

Therefore, while practitioners are not advocating to be diagnosticians, it seems that multiple disadvantage and

co-occurring needs alongside autism affects participants’ confidence as they do not know how to respond to traits that could be from a variety of origins. This is further compounded by a hesitance to have conversations around autism with clients, due to lack of diagnostic qualifications, and not wanting to label clients and cause harm. As one participant highlights, however, that autism-informed practices could benefit everyone.

There are some really straightforward adaptations that can be made to help autistic people and services, they’re just not done consistently. It would be great if there was a training course that addressed the quick and low cost changes that we can all make, which quite frankly benefit all humans not just autistic ones!

There is a lack of awareness about autism within services

Participants suggest that homelessness services broadly lack awareness about autism, and imply that it is not something that staff talk about, or that clients are screened for or asked about. This seems to be impacting staff confidence when having conversations and working with autistic people.

Autism awareness has not been a feature of services I have worked in and I am embarrassed to say that I have not prioritised this as an area of self-learning to look into (until now). I have almost no knowledge about autism or how to work with those who are or may be autistic. I have never worked with a client known to have autism.

There is a knowledge gap around autism in homelessness services.

I feel autism isn’t really something that comes up when clients are referred into our service – the focus will typically be on mental health and substance use.

Autism and homelessness training and resources available to participants

Most participants felt that current training and resources were not sufficient in equipping them to support autistic people experiencing homelessness.

Figure 10: Participant responses to how well they perceive their organisation’s training or resources equip them to work with autistic people experiencing homelessness

Figure 10 highlights that 42% of participants felt that their organisation’s training or resources do not equip them to work with autistic people experiencing homelessness, compared with 26% suggesting that their organisation’s training successfully equips them.

When asked about what training and resources are available, the following themes were identified from qualitative participant responses:

a) There isn’t any training/the subject is vaguely mentioned in other sessions

b) The participant did their own research

c) There are resources and training provided outside of the organisation within which they work

d) There are resources and training provided within participants’ organisation

There isn’t any training/the subject is vaguely mentioned in other sessions

A core theme that many participants suggested is that there are no resources or training about autism and homelessness, with some participants noting that they also lack access to specialist practitioners from whom they can seek advice. One participant notes:

In my experience this is a neglected area of professional practice, with little in the way of diagnostic resources and guidance available. I have had to but my own books to learn anything, and there is no one to turn to for advice. What seems clear to me is that ND people are very much individuals with their own stories and many of our clients need the benefit of experienced professionals who have highly developed practice in working with them. This is simply not available.

Any training that does touch on autism and homelessness is not perceived by participants to be in enough depth:

In mental health training different problems are brushed over so you get a short overview. However, if you are like myself and are a general nurse (NP) working with those that are homeless I already have that understanding and need something that bit more in depth which is not available for general adult nurses only MH nurses.

I have a personal training budget but finding relevant training at the right level is hard.

The participant did their own research

Several participants said that they did their own research, through books or finding training on autism or ADHD outside of what is provided from the organisation.

There are resources and training provided outside of the organisation within which they work

Of the resources and training mentioned by participants outside of the organisation within which they worked, a key resource referred to is the Autism and Homelessness Toolkit – but this was only suggested by 10/186 participants. While this resource was not enquired about directly, for some they said it was useful, without giving explanation, but the fact that it was not mentioned by a greater number of participants may suggest that it is not well-known or utilised.

Some participants said that there is e-learning from different organisations, other services invited to train their team if there is a high level of need, and access to a community of practice where this topic has been spoken about.

Other specific training courses mentioned by participants included LNNM training, iHasco training, HHCP and CAAS training, Centre for Homelessness and Practice training and training run by the National Autistic Society. One participant mentioned being an NHS National Autism Programme trainer “Certified to train NHS professionals in recognising and supporting autistic people.”

However, it remains unclear how much these resources delve into homelessness and autism specifically. A final facet of training provided from external sources, mentioned by one participant, was that they have access to specialist practitioners who can speak to their team, but no formal training provided by their organisation.

I have access to a psychologist and psychiatrist who have been very helpful is suggesting ways to work with autistic clients.

There are resources and training provided within participants’ organisation

Many participants noted training from within their organisation, but these responses seemed to be only from NHS staff in specialist roles.

Many NHS practitioners mentioned the Oliver McGowan training as an important resource, but again this does not focus on the intersection of autism and homelessness, and one participant noted that while it is useful they did not feel it:

Appropriately highlights the complexity and diversity of ASD.

Other resources mentioned included The Sycamore Trust’s autism awareness training, in-house neurodiversity training, service champions, and clinical guidance for specialist services, including publications, the NICE guidelines, webinars, conferences and professional networks.

A further critique presented by participants was that there is training on autism available, but it is online and not mandatory. One participant said that their local authority provides resources about autism, but not autism and homelessness.

They do not have specific focus on women’s presentations and how that might differ to when neurodiversity intersects with trauma.

The next section will seek to explore what changes participants would suggest should be made to the training and resources available in greater detail.

Proposed changes to training and resources

This section explores participants’ views on the training and resources available to them, whether they adequately support them to provide care to autistic people experiencing homelessness, and what changes to training and resources they would want to see.

Figure 11: Participants responding to whether they believe changes are required to training and resources about autism and homelessness

95% of participants felt that change was needed to improve training and resources for services working with autistic people experiencing homelessness (Figure 11).

In the qualitative follow-up to the data presented in Figure 11, participants suggested a plethora of changes that could be made to training and resources focused on autism and homelessness, which were analysed to encompass the following themes:

a) Neurodiversity and autism training is not prioritised – there needs to be more training in this area, and it needs to be

mandatory for all staff

b) There are specific topics that participants would want training to cover

c) One-time e-learning is not enough; communities of practice, in-person training and continued spaces to reflect and learn are important

d) Training alone is not enough – changes to training need to be coupled with systemic change

These themes are explained in more detail below.

Neurodiversity and autism training is not prioritised – there needs to be more training in this area, and it needs to be mandatory for all staff

Participants suggested that there is a lack of training in their organisations and across the system more widely about autism and homelessness, with one participant noting:

I feel that neurodiversity is a bit of an after-thought at the moment within my organisation. I am aware that many clients experience neurodiversity and this creates barriers in their ability to communicate their needs effectively with others, it can also be tied in to substance use so I think it is an area that requires better understanding of how it interlinks with homelessness.

Another participant speaks to the prevalence of autism and homelessness co-occurring, and therefore the level of training and resources needed to reflect this.

I think there should be more training available around neurodivergence and autism – especially as so many of our clients self-identify as autistic or neurodivergent, and many have a diagnosis. I do not feel there is enough training or resources to reflect this. I think that autism can have a huge impact on the level of trauma homelessness can cause, and it needs to be given more weight within services – meaning that we need a higher level of training and resources.

One participant suggested that the lack of prioritisation of autism within homelessness settings is not only widespread, but within senior leadership, and identified a lack of commitment to developing appropriate training.

Training needs to be offered to all staff, but I am having trouble persuading senior leadership to invest in developing and to provide one (based on cost).

An emergent theme in the data that many participants recognised is that training about autism and homelessness needs to be mandatory, core training for all staff, not an optional course, where it does exist.

We need mandatory neurodiversity training for any workers especially those in the homelessness sector. We work with a population where we see a massive overrepresentation yet massive underdiagnosis.

Participants also suggested there needs to be:

A universal understanding of the commonality of brain injury/TBI/neurodiversity/trauma, indicating that conditions that intersect with homelessness needs to be understood, and participants also noted that this needs to reach all who support and fund projects, including leaders and commissioners.

Diverging from this, some participants suggested that the profile of autism and homelessness is slowly being raised – for example through:

Staff neurodiversity networks who are working to raise the profile and training, and there have been training available locally and talks at conferences, this is still a new and recent area and it still needs to improve.

Therefore, while in the previous question it seems that the NHS has greater provision of autism training, there is still very much the need for understanding of autism and homelessness, and training to be more widespread within the third sector and local authorities.

There are specific topics that participants would want training to cover

Participants suggested a wide range of subjects that they would want autism and homelessness training to cover, including:

- How autism presents and what autism traits look like; spiky profile of autism

- How to support someone seeking a diagnosis

- How to recognise autistic traits when someone is using substances and has co-occurring mental health issues

- How autism intersects with homelessness – both the prevalence, causes, perpetuating factors and how to support someone

- How to support someone who is autistic and has co-occurring needs

- How to adjust language use

- Challenges faced by autistic people when placed in hostel accommodation

- Intersecting topics such as brain injury, ADHD and trauma

- Pathways for support available (diagnosis, support, housing)

- Trauma informed practice adapted for autism and other conditions

- Communication challenges

- How to do an assessment that takes autism into account

- How to use a screening tool

- How to include information about autism in referral documents and conversations with partner agencies

- How to work with partner services to provide better support for autistic people

- Advocacy – including understanding rules and regulations; with a view of how to prevent eviction, arrears and abandonment of tenancies

- What is masking?

- Autism and substance use

- Autism and trauma

- Challenges faced by autistic people experiencing homelessness

- Good practice for support

- What to do if autistic traits are recognised

- Literature and statistics bout prevalence of autism for people experiencing homelessness

- Co-production and including people with lived experience in developing and delivering the training to centre their voices – maybe including the people in their lives too and how they support the autistic person

- How to adapt services and service settings – practical approaches; how services can better meet the needs of autistic people rather than asking the client to adapt to service standards

- Resources to refer to

- Autism and all areas of multiple disadvantage

- Case studies

- More specific training on autism, rather than neurodiversity as an umbrella

- Internal experiences of autism

- How to discuss autism support with an individual that is unsure about accessing support and diagnosis, how to approach initial conversations

- How to navigate priority need and homelessness applications

- Ensuring there is nuance – not encouraging labeling

- Intersectionality and gender-informed approaches: what autism looks like for women; how autism informs a person’s approach to relationships (recognising risk), sex (the sale of sex), substance use and safety.

- Managing conflict

- Supporting autistic people who cross boroughs

- How to help autistic people to navigate the ‘system’ – which is complex and difficult to navigate

- Effective tenancy support for autistic people; understanding how autism can affect daily living skills

- Autism and potential vulnerability to exploitation

- Who to turn to when a case feels ‘stuck’ – which specialist services can help?

- A list of resources for the autistic person – including peer support groups

- Tangible changes to be made to physical environments and sessions with clients (e.g. quiet rooms)

- Metropolitan Police Autism Alert Card and how to use it and introduce it to clients

- Care Passports

- How to get access to fidget toys and ear defenders – physical aids and why they help

- [From a Clinical Psychologist]: “I’d appreciate some adapted ADOS training that covers how you can assess and support with these complex cases, particularly when there isn’t anyone to corroborate developmental history”

- Reasonable adjustments that can be made

These were the themes and suggestions from participants which could form the basis of future training courses, but the authors would suggest that a limitation of this section is that the survey was not aimed at those with lived experience of homelessness and autism. Therefore, the client/patient voice must be included to develop training that is suitable for supporting this client group.

Participants also voiced that they did not want training to feel as though it was further stigmatising or labelling individuals.

We do not want to label behaviours or ways of being as autistic because services find someone difficult or unusual. People who are or have been homeless are an extremely diverse group of people who are already objectified, medicalised and others.

The authors would like to suggest that spiky profile of autism needs to be represented in training. Participants strongly suggested that training needs to be nuanced, rather than encouraging stereotyping of autistic traits, so that support needs can be better understood.

It was also suggested that more in-depth training, and continued training, could have significant benefit to services who would then potentially be better able to understand clients:

It would be helpful to provide advanced training/workshops to cover all of this, as they can sometimes seem to be “too complex” for service providers to understand.

One-time e-learning is not enough; communities of practice, in-person training and continued spaces to reflect and learn are important

A core theme within this question was that participants suggested that one-off training is not sufficient.

There are minimal resources so I would like to see something much more bespoke developed, I would like training to be ongoing e.g. through reflective spaces. Training in this area is not a one-and-done issue. It requires specialists and autism/homelessness champions in teams at the very least.

Participants expressed that in-depth training is important:

I would also like the see robust autism training available, as in not just a half-day course, but a 1–2 day course so participants have a good understanding of autism and not just a surface level training.

The modality of the training was also important – no participants suggested that e-learning was enough or better than in person, yet many proposed that: “face-to-face training would be better” giving the rationale that they can “ask questions as we go along.”

Training alone is not enough – changes to training need to be coupled with systemic change

Whilst training needs form a large part of this survey, the authors are keen to purport that training is not sufficient for meeting the needs of the client group, and to acknowledge that the homelessness system and services are already under immense pressure. Therefore, to caveat this section, the authors want to suggest that training should be developed to aid staff, but that systemic changes also need to be advocated for and implemented to truly meet the needs of this client group.

These sentiments were echoed by some participants, where they suggested that:

There is no point in looking at training when there are no pathways for these specific people to be fast tracked through services etc.

And:

Training on specific issues relating to autism and homelessness… needs to be accompanied by funding of actual services.

Provision of specialist services in London

This section exclusively explores data around participant awareness of specialist services and the details of these services.

Figure 12: Participant awareness of services or projects that support autistic people experiencing homelessness

81% of participants were not aware of any specialist services or projects in their area that would work with autistic people experiencing homelessness (Figure 12).

Participants were asked to provide information about the specialist services available to them. This information may be useful for readers of this report, but please note that this information is only accurate as of September 2024, and this is not an exhaustive list, but only those from the responses given by participants which the authors were able to verify online.

Specialist services in London identified by participants:

- Mind in Haringey have a centre for autistic people

- Autism Hounslow

- Change Communication Westminster – Speech and Language therapist is able to offer case support consultations and individual sessions with clients, alongside training for services. Faster assessments have also been secured.

- South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust have a Transforming Care in Autism team – they have developed a resource called a ‘communication passport”

- Psychiatry within Turning Point in Westminster – all clients are screened for autism

- CDARS Neurodiversity Support Programme Kingston

Specialist autism services meeting the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness

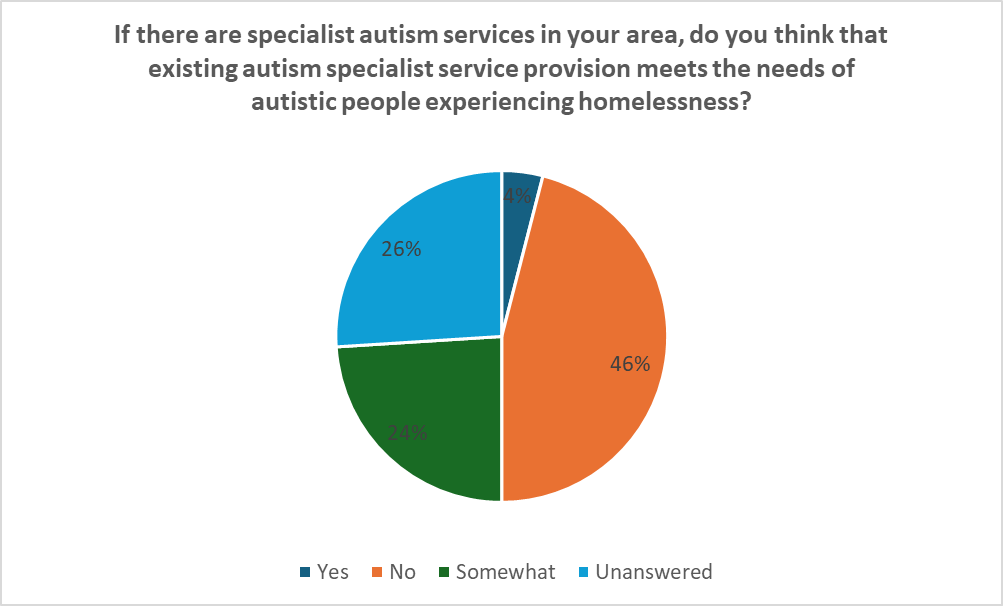

Figure 13: Participants reporting on whether they believe the specialist autism services in their area meet the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness

50% of all participants, from the sub-section of participants who were aware of specialist autism services in their area, suggested that existing autism services did not meet or only somewhat met the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness (Figure 13).

If participants had answered ‘yes’, that there are specialist services for autistic people experiencing homelessness within the area that they work, they were then asked whether those services meet the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness and why. The answers were analysed and grouped into the following themes:

a) Specialist services do not specialise in working with people experiencing homelessness or multiple disadvantage

b) Specialist services only provide access to diagnosis – there is a lack of post-diagnostic support due to services being stretched

These themes are explored in more depth below.

Specialist services do not specialise in working with people experiencing homelessness or multiple disadvantage

Where participants noted that there were specialist services in their area, they suggested that these services were specialists in working with autistic people, but not those experiencing homelessness.

Although open to all adults it seems that homelessness is not their specialty.

I have worked with autistic patients my whole career, am neurodivergent and have close relationships with autistic people but I feel there are no services for autistic people experiencing homelessness, certainly none I know of.

Participants suggested that this may create barriers for clients when accessing this support.

I think it is difficult sometimes as some services don’t have the full understanding of homelessness and how our clients interact with people especially someone with autism who is experienced homelessness or gone through the homeless pathway, does struggle with appointments anyway and engaging so some services are very quick to close the clients cases without even trying to engage with them.

It was also highlighted that there are other difficulties relating to intersectionality and systemic barriers to accessing specialist autism services, meaning that participants do not feel that these services meet the need of autistic people experiencing homelessness.

Long waiting lists, no post diagnostic support, poorer experiences for BAME people and women (especially young women), lack of recognition of intersection between autism and LGBTQIA+ (especially problematic for autistic women and non-binary people who seek women only services), not wanting to support people with co-occurring homelessness and substance use.

And:

Services often dismiss the experiences of people experiencing homelessness or decline referrals stating issues are because of substance use or lifestyle. Services are not accessible and do not work in conjunction with other specialist services.

They don’t meet that of the most able, most advantaged people never mind those facing multiple disadvantage.

While some participants were critical of specialist autism services, the authors would like to highlight that point b) in this section, below, suggests that some participants understand that this may originate from a lack of funding and services being stretched by increasing demand.

Specialist services only provide access to diagnosis – there is a lack of post-diagnostic support due to services being stretched

Some participants seemed unsure about what local autism services provide.

I do not know what our local autism service provides – unsure if they provide any support or just diagnosis.

This was caveated by the suggestion that the inability to meet the needs of the client group is due to:

Resources [being] stretched, and the current government doesn’t provide enough funds for these resources.

And:

Thresholds for specialist services accepting a referral seem very high and are often declined. I can’t see obvious reason(s) for why that is, beyond capacity and services that are already overstretched.

Mainstream/non-specialist autism services meeting the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness

Figure 14: Participants reporting on whether they believe the specialist autism services in their area meet the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness

14% of all participants reported that they believe mainstream services meet the needs of autistic people experiencing homelessness (Figure 14).

The survey asked whether, in the absence of specialist service provision that participants were aware of, mainstream services meet the need of autistic people experiencing homelessness. The following themes exploring why were identified:

a) Mainstream services are not equipped or trained to work with autistic people or those experiencing multiple disadvantage – services lack flexibility, and the settings are not set up to accommodate autistic people.

b) Specialist homelessness services exist – including specialist multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) – which helps mainstream services.

c) Supported accommodation and housing pathways and support does not support the needs of autistic people

Participants’ views on these themes are explained below.

Mainstream services are not equipped or trained to work with autistic people or those experiencing multiple disadvantage – services lack flexibility, and the settings are not set up to accommodate autistic people

One of the key themes in answer to this question around whether mainstream services meet the need of autistic people experiencing homelessness, was the suggested lack of flexibility and awareness of autism. One participant encapsulates these ideas:

Services are often set up in a way which expects individuals to conform to their needs. For example, if a client with autism (which is often not known by services or goes undiagnosed) finds it difficult to have a discussion in a noisy and often chaotic environment, they could be seen as not engaging.

Within health settings, autism is often not considered, and any referrals are often sent to mainstream services where clients might not meet the ‘criteria’. Mainstream services are also less flexible when it comes to missing appointments or working within the context of an individual having multiple support needs.

Another participant echoed this sentiment:

Homelessness pathway is too rigid and inflexible and places an expectation of conformity and co-operation on the client that many people, those with MH issues or especially autism for example, are unable to meet. The system is not properly person-centred there is very limited understanding of autism and too often the expectation is that client change to fit criteria and pathways rather than the system being flexible enough to support everyone.

The varied presentation of autism further necessitates flexibility, participants indicated.

[Whether the mainstream service meets the needs of autistic people] depends on the person with a diagnosis of autism surely. They are not a homogenous group.

The authors would like to point to later sections that speak about systemic changes that participants would want to see, which explore how to remedy this proposed lack of flexibility.

Specialist homelessness services exist – including specialist MDTs – which helps mainstream services

When being asked about mainstream services, some participants wanted to speak about specialist services that do not focus on autism, for example, specialist homelessness mental health teams. Participants advised that these services were helpful in meeting the needs of the client group. Three participants explicitly spoke of RAMPH teams, which are specialist multi-disciplinary outreach mental health teams for people experiencing homelessness.

One participant suggested:

The RAMPH team provides excellent mental health service for people who are rough sleeping which, although not specifically for autism, would provide psychiatric assessment and if suspected autism would refer on to appropriate services.

While this was not explored in more detail within the survey, further research could consider more detailed explanations around why these services are an asset to mainstream services when needing of autistic people in homelessness settings. Based on the overall data from this survey, the authors would speculate based on this data that having access to clinically trained NHS staff, who may not be autism specialists, but may have training in psychology, nursing and occupational therapy, helps non-specialist homelessness services to more adequately meet the needs of autistic people.

Supported accommodation and housing pathways and support does not support the needs of autistic people

Many participants noted the seemingly inadequate environments and systems that surround the homelessness pathways, which were viewed as compounding autistic people’s difficulties. Participants explicitly mentioned hostels:

For many people experiencing autism, living in a chaotic, loud, unpredictable, shared hostel setting carries many potential triggers and challenges. It is challenging enough to try to communicate your wants and needs to a neurotypical person, but even more so if you are surrounded by neighbours that might also be neurodiverse on top of using substances, may present as hostile or inconsiderate of another person’s wants/needs.

However, other stages of homelessness pathways, transitions and housing shortages were also highlighted:

It is so difficult to transition to independent living when supported living is in high demand and not available, often people fall into arrears, it impacts mental health and their anxiety, unhealthy eating, social isolation and risk of being victims of crime.

They build a trust with [our service] and then they are moved out of borough and then these people live in social isolation as they struggle to build friendships or get out and do things as they need the support.

The systemic changes suggested by participants to remedy the issues highlighted are explored in the next section.

Systemic changes suggested for the system to better support autistic people experiencing homelessness

The final structured question asked participants to detail the changes they would want to see in the system to allow autistic people experiencing homelessness to be better supported. The following themes were identified from participant accounts:

- Recognition and awareness of the prevalence, presentation and support needs for autistic people, and for co-occurring autism and homelessness, with nuanced understanding

- Flexibility and accommodation of autism within services, both in the environment and in interactions with practitioners

- Co-producing change with autistic people

- Gender-informed approaches and increased understanding of women’s experiences of autism and homelessness

- A need for commissioners and funders to better understand the needs of autistic people, thereby improving the identification of and commissioning for appropriate outcomes

- Structural changes to pathways for support – access to rapid and flexible diagnostic assessments, specialist open-ended support and resources, preventative support, amendments to priority need and statutory duties, and appropriate accommodation and pathways

- A joined-up approach throughout the system – joint working and sharing information between services, and pooled funding

- Recurrent in-person training for all staff about autism and homelessness

These themes are explored in more detail below.

Recognition and awareness of the prevalence, presentation and support needs for autistic people, and for co-occurring autism and homelessness, with nuanced understanding

Some participants felt they did not know that there were any links between autism and homelessness, and some believe they have never worked with an autistic person who is experiencing homelessness. This led to participants asking for more information.

I have not worked with a single service user with a formal diagnosis of Autism in the 3+ years I have worked with the homeless population in London. Is this a hidden issue that practitioners need to be aware of?

Diverging from this, other practitioners seemed to be aware that autism and homelessness may be linked, but believe that there is a lack of awareness and attention around the issue within services.

Just as much care and attention is given to other barriers such as substance use, alcohol, mental health. The same needs to be given for autism. This very much could inform the types of accommodation built, the types of service on offer, developments in tools, developments in ways of working etc.

In my experience this is a neglected area of professional practice, with little in the way of diagnostic resources and guidance available. I have had to buy my own books to learn anything, and there is no one to turn to for advice. What seems clear to me is that ND people are very much individuals with their own stories and many of our clients need the benefit of experienced professionals who have highly developed practice in working with them. This is simply not available.

ASD specific services – putting people with ASD as a primary need in with others who have SMU and substance use etc makes them more vulnerable to using substances. Consider services that are ASD specific and laid out in a way that is ASD friendly.

There were questions raised by participants about how to support these changes with research, how to look at preventative measures to prevent homelessness and multiple disadvantage.

Better reporting and recording of information about autism and homelessness [in services] should influence services and commissioning, to promote prevention of homelessness.

There has been much ground gained by researchers in the field of neurodiversity. This information needs to cascade down to all. Local authorities need to change their assessments for care and support needs to reflect the real issues and risks faced by people living with ND.

Flexibility and accommodation of autism within services, both in the environment and in interactions with practitioners

A prevalent theme within the data collected from this survey was that many participants advocated for existing services to be more flexible, more accommodating of autism, and to make changes to make the services more accessible for autistic people. Participants also suggested that this is compounded by accessibility barriers for people experiencing homelessness. The changes suggested by participants, focused the physical environment and support provided, alongside tangible practice-based changes such as introducing screening tools. The suggestions are listed here as they could be utilised as service recommendations:

All accommodation based services need investment into buildings and physical environment: the noise, lighting, smells, the way information is provided and shared, should have access to aids as heavy blankets, noise cancelling headphones, fidget toys, speech devices, have sensory rooms and spaces etc. and workers trained in supporting residents relationships in shared accommodation.

Recognition that autism is not mental health difficulty, nor learning difficulty (both can co-exist) and the aim is not to make person to present in a less autistic ways or worse cure them of autism but provide support that is not re-traumatising and person centred.

Autistic people are social creatures that need their community and relationships as much as everyone else but their social networks might look differently to how non-autistics socialise (e.g. online community).

Providing psychologically-informed environments.

Be flexible with people missing appointments and who understand the other support needs that homeless people have.

Systems need to be adaptable towards the needs of each individual rather than expecting clients to meet the need of the service.

For staff in the housing teams to take into account the individual needs of people with autism. Completing forms and providing evidence can be such a stressful experience, they need to be clear what they can do to support clients or who to go to for help. Clearer guidelines for how Autistic diagnosis or traits are taken into account with medical assessment.

Low barrier, easy access support for diagnosis and ongoing support in the context of patient’s situation. Services to come out and assess where patients are at rather than hoping they’ll come to a building-based clinic.

More clarity around how procedures will work for clients – work, particularly with local authorities tends not to be collaborative – you are assessed and then have a plan delivered to you with very little explanation along the way.

Dedicated quiet/sensory spaces in services.

We are now screening for autism in new assessments using the AQ10 as recommended by NICE. We are then able to make an onward referral to the local adult autism service and have negotiated for a quicker response time.

Better autism screening and assessment practices in all services… [in my borough] we have a fabulous psychiatrist who screens every homeless person he engages with.

Autism screening at the very start of engagement with people as part of a general health screening.

To fully support people rough sleeping services would need to be able to go on outreach, work in hostels or from other build-based services.

There should also be options to access service both face to face and virtually and this is not always a choice open to people.

I work in partnership with specialist mental health services, as well as having experience of going via GP for support, so I feel able to signpost and/or raise this with professionals – however, I think there are barriers to accessing the support in a way which is accessible for people who are experiencing homelessness.

Co-producing change with autistic people

A core theme suggested by participants is that changes made to services, at all stages of the commissioning and service delivery process, should be informed by co-production and participation principles. Participants said that they wanted to hear from autistic people in training sessions, and to understand the nuanced experience of autism first-hand.

Gender-informed approaches and increased understanding of women’s experiences of autism and homelessness

The authors noted that gender-informed approaches and autistic women were topics that were mentioned by a few participants, but this was not a prevalent them. However, this may have been influenced by the survey not explicitly asking about it, or by participants’ lack of awareness around the differences in presentation. Nevertheless, the authors want to put emphasis on this theme as it is important to represent the intersectional needs of autistic people. One participant noted:

I would like much higher understanding of the extent of gender-based violence amongst autistic women (needs autism specific VAWG services) and that autistic survivors present differently.

A need for commissioners and funders to better understand the needs of autistic people, thereby improving the identification of and commissioning for appropriate outcomes

Participants suggested that funding and commissioning reporting and expectations do not always match what the service is able to deliver, or what is helpful for the client in terms of meaningful outcomes. A change that was suggested is having greater congruence between meaningful and measurable outcomes, what change is realistic and helpful for the client group, commissioner expectations, and how the service provides support.

Some expectations of commissioners/funders as to what services can achieve are often so unrealistic and far away from what autistic people want and need that it leaves staff stuck between the actual needs, wants and goals of their clients and evidencing outcomes that commissioners and funders want them to demonstrate.

Funding is often in 1 or 2 year ‘chunks’, just as someone gets used to a service it closes!

Participants also suggested that it is important to take into account the significant demands that services are faced with.

We have so much on our plate already, staff often gets overwhelmed by the expectations around managing client behaviours, clients who are getting more and more complex.

Structural changes to pathways for support – access to rapid and flexible diagnostic assessments, specialist open-ended support and resources, preventative support, amendments to priority need, and appropriate accommodation and pathways

A near ubiquitous theme within the qualitative data was the ask for structural changes for autistic people experiencing homelessness. This ask was divided into key sub-themes: access to rapid and flexible autism diagnostic assessment, access to specialist open-ended support and resources, preventative support for homelessness, amendments to priority need, and autism appropriate pathways and accommodation. Participants’ accounts surrounding these sub-themes, and other ideas suggested, are detailed below.

Access to rapid and flexible autism diagnostic assessments:

Shorter waiting lists for assessments.

Better identification and fast track of homeless people with autistic presentation.

Quicker assessment routes for homeless clients. Preferable outside a borough restricted approach requiring stability and connection.

More multiple disadvantage trained psychiatrist/assessors or people able to do assessments co-located with homelessness services (such as outreach services day centres and hostels).

A dedicated autism assessment services that includes speech and language therapy.

It is very difficult for homelessness services to tailor their service without a clear diagnosis.

In [the borough I work in] we have negotiated a faster assessment service, with the added flexibility of autism services assessing where patient is receiving usual care.

Currently patients have to engage with the first assessment with an opt-in letter which is a big barrier at times.

Awareness of the specific issues those with autism experience and the compounding effects experiencing homelessness adds to this. The barriers to getting a diagnosis means if they haven’t been diagnosed then these difficulties aren’t acknowledged in their housing application and medical assessment.

The main issue is the very long wait for assessment and diagnosis and what support is available in the interim.

We have a number of people experiencing homelessness, who display autistic traits and maybe self-identify- but there is such a lack of understanding of autism needs in homelessness. We have to refer to mental health services and GPs, but rarely can find agencies to support with assessments and diagnosis. Navigating homeless sector provision is already complex and support for those with autism is sadly not readily available.

I often see clients with autistic traits, no diagnosis and no pathway for getting them diagnosed. They can be extremely vulnerable, but we’re frequently asked to confirm if they have a diagnosis and adult social care in particular don’t like a presumed or self-identified diagnosis and always want something documented on a GP record. It’s another barrier and stops vulnerable clients getting appropriate support/accommodation.

Access to specialist open-ended support and resources:

Support to get a diagnosis and appropriate counselling or coaching support.

Bespoke services for people who are homeless, autistic and have other support needs, i.e. substance use.

Autism services gender and multiple disadvantage informed (i.e. open to clients who are also using substances for example or don’t attend appointments consistently).

Autism tailored counselling and psychology – recognising prevalence of trauma for autistic people – specialist psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, psychotherapists etc.