Health Inequalities, Population Health & Proactive Social Prescribing

What are health inequalities?

- Health inequalities, or more accurately, health inequities, are avoidable, unfair and systematic differences in health between different groups of people

- There are many kinds of health inequality, and the term is used in various ways

- When we talk about ‘health inequality’, it is useful to be clear about which measure is unequally distributed, and between which people.

- Health inequalities are widening in London and five London boroughs in top 10% most deprived boroughs in UK.

- With the cost-of-living crisis, health inequalities are likely to get worse.

Examples of health inequalities can be found in this government report.

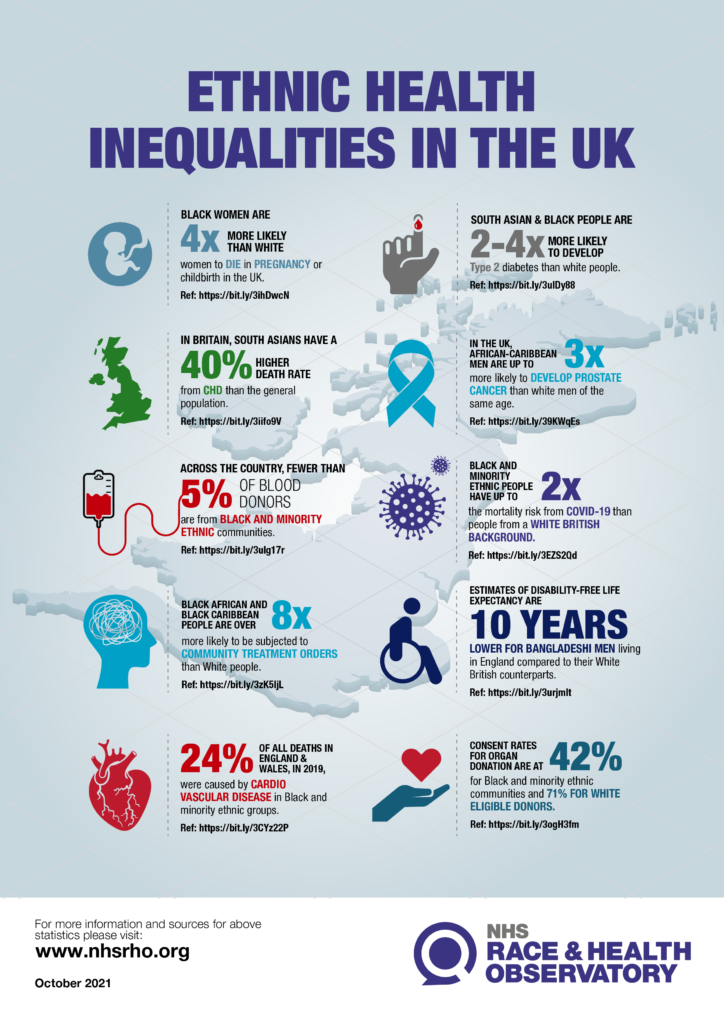

Ethnic minority communities experience some of the worse health inequalities and they are also under-reached in social prescribing.

There are multiple ways the 3 roles can be used to reduce ethnic health inequalities:

- Care coordinators proactively calling and recalling patients for health checks, annual reviews and screening to reduce inequalities in outcomes from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and other long-term conditions.

- Specialist social prescribing link workers to support ethnic minority women during pregnancy and in the postnatal period to reduce maternal health inequalities.

- Mental health specialist social prescribing link workers to increase trust, engagement, compliance and reduce inequalities in access, outcomes and experience of mental health services patients.

- Health and wellbeing coaching using culturally and linguistically relevant resources and tools.

- Recruitment of the 3 roles from ethnic minority communities as part of building trust, engagement, and a responsive personalised care workforce.

- NHSE has produced an e-learning module to support culturally responsive social prescribing which can be accessed here.

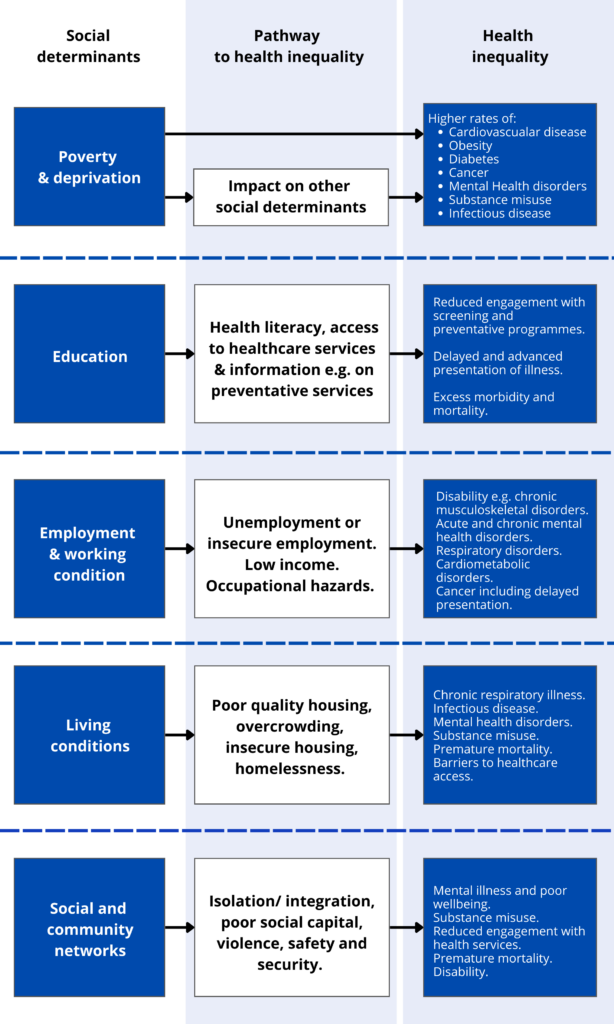

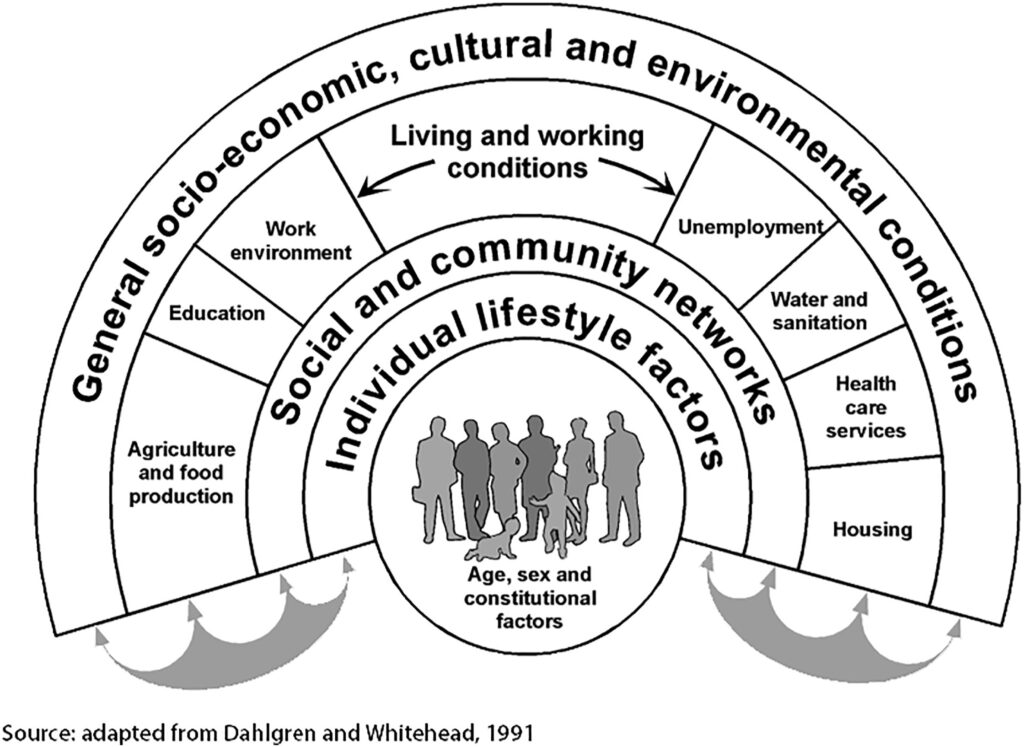

- Wider factors (the social determinants of health) are critical in shaping the health of patients and populations, even more so than the biomedical factors that healthcare systems, education and training conventionally focus on

- Research shows that the social determinants of health (SDoH) can be more important than health care or lifestyle choices in influencing health

- Numerous studies suggest that SDH account for between 30-55% of health outcomes. However, in areas of deprivation and for patients with mental health disorders and/or multimorbidity, this statistic is likely to be much higher. Some sources determine the contribution as higher, for example up to 80-90%

- Estimates also show that the contribution of sectors outside health to population health outcomes exceeds the contribution from the health sector, which emphasises the importance of multi-agency partnership working and community development.

The 3 personalised care roles form an important part of a PCN’s strategy to address health inequalities, but they must be effectively embedded.

| Five key principles for using the 3 personalised care roles to reduce health inequalities | |

| 1.Address the social determinants of health | 1 in 5 GP appointments focus on wider social needs with a higher proportion in more deprived practices that are also most likely to be under-doctored.

The personalised care roles link patients with these wider social determinants of health e.g.

|

| 2. Build community intelligence | Personalised care roles can take the time required to understand the local population, their needs and priorities in order to shape and provide care that is relevant, responsive, appropriate and acceptable.

|

| 3. Work with specific groups who are experiencing inequality in access, experience or outcomes | Overcome barriers and close unacceptable gaps that exist in health and care through proactive outreach and trust and relationship building with under-served patient groups.

|

| 4. Facilitate joined up working | Connect with community assets and resources, strengthen community development and facilitate joined-up working and whole system approaches to tackle health inequalities holistically, collaboratively and sustainably.

|

| 5.Personalised care is an intrinsic tool for PCNs in community recovery | There is a significant ARRS underspend in London and funding and support is available to grow these teams

|

Key ingredients to optimise the working environment to ensure the three roles work well with practice and PCN teams

- The roles need to feel a sense of belonging in the team.

Include them in MDT meetings and any practice and PCN wide meetings. - Set up practice and PCN wide meetings for the personalised care ARRS roles, so they can discuss how best to work together and share best practice.

- Deliver regular training, communications, and meetings where current and new staff are educated on what the roles do, how to refer to them, what they do and not do and how they can be reached.

- Ensure the roles have access to GP IT systems and have clinic templates set up. All three roles are patient facing and should have ringfenced slots to book patients in and clinic space.

- Allocate a GP or clinical supervisor for the roles, who can provide regular ringfenced supervision and ad hoc support as well as direction regarding working with different patient cohorts.

- Give the roles time each week to spend on understanding the wider practice workings, training, connecting at an ICS and regional level, and connecting with the community, patient groups and adjacent services e.g. care homes.

- The Health Inequalities DES supplement outlines the role of PCNs in reducing health inequalities and the responsibility of a HI lead.

Top Tips for PCN Health Inequality Focus

- Get support from other organisations

- Name a lead & attract fellows

- Understand your PCN’s HI needs

- Work with your community FEEDBACK

- Make it the core of your PCN targets

- Use the resource you have and advocate for more.

From population health webinar- Aaminah Verity, Health Inequalities Lead at NLPCN.

PCN Health Inequalities Lead

- One of the requirements in the TNHI DES contract is for PCNs to appoint a Health Inequalities (HI) lead to work on priority areas including:

– Learning Disabilities (LD) register health checks

– Serious Mental Illness (SMI) physical check

– Ethnicity recording

– Identification of populations experiencing HI by PCNs. - A named HI lead in each PCN can work with the personalised care roles to map and address local unmet needs and coordinate HI activities

- The HI lead does not have to be the PCN CD, it can be any suitable clinical or non-clinical person

- ICSs are expected to create a peer network of HI leads, provide analytics for PHM, support co-production.

Some challenges with embedding a PCN HI lead

- Many PCNs in London have not yet appointed an HI lead with a formal role and/or strategy

- We have heard PCN leaders and current HI leads reporting challenges with:

– Understanding the nature and purpose of the roles- creating job descriptions and job plans have helped with this.

– Adequately funding and resourcing these roles- a checklist and case study below may be used for ideas.

– HI leads not feeling supported- some HI leads are exploring ways of setting up a support network.

Checklist for embedding and working with a PCN health inequalities lead

- Support and commitment from PCN leadership- this is essential

- Ensure there is a named health inequalities lead who is a visible point of contact for health inequalities issues in the PCN

- Remember, an HI lead can be any suitable clinician and does not have to be a GP

- Ensure the role is funded with protected time and a clear job description and with opportunities and investment in training on health inequalities

- Use personalised care roles creatively to bridge the gap between primary care and the community and partner anchor systems to effectively address SDoH e.g. allocating time for community development and outreach work to build links and support referrals

- Adequate time to plan strategy, work with and supervise ARRS roles where needed

- Utilise asset-based approaches – with support from ARRS roles who have good local knowledge:

- Map local assets and resources

- Community engagement: join or form a stakeholder group or community forum with representation from local community groups, leaders and across agencies

- Co-produce solutions to address local health inequalities

- Outreach work: identify and reach out to underserved patient groups and communities.

- Data-driven approach; develop knowledge, data and dashboards to identify patient cohorts experiencing HI and progress national targets (e.g. ethnicity recording). See section on population health and proactive social prescribing for further information

- Support funding for local community initiatives; without investment in community development the impact of the work of a HI lead is limited. Looking for co-commissioning models such as with local authority, community grants and PCN development fund

- Training opportunities and peer support for HI leads coordinated by ICSs

- Advocacy to raise awareness of health exclusion and inequalities and approaches for tackling them.

Resources:

-

- Health Inequalities eLearning modules via the RCGP Health Inequalities Learning Hub

- Health Anchors Learning Network

- Targeted support from NHS England’s Health Inequalities Improvement team.

Case Scenario

HI lead working with the 3 PC ARRS roles

Dr C is a GP and HI lead for her PCN. She spends 2 sessions a week working and delivering on her PCN strategy to address health inequalities. As part of this, she meets with her ARRS roles for 1 hour a week. A key area of health inequality identified by her PCN is low uptake of health checks in ethnic minority communities. The care coordinator is involved in identifying patients who need health checks and books them in with a healthcare assistant. The CC also works with the SPLW to identify organisations and centres these health checks can be carried out in the community as part of outreach engagement. During the health check, if lifestyle issues are identified e.g. low activity and poor diet, these patients are referred to the HWbC who runs group consultations.

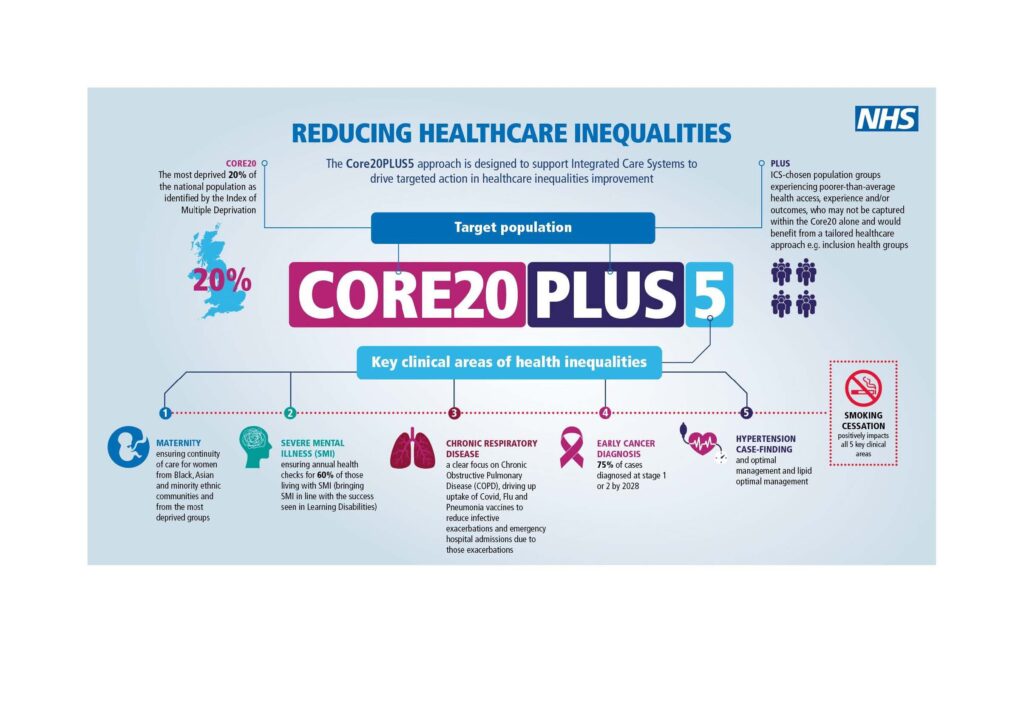

Core20PLUS5 is a national NHS England and NHS Improvement approach to support the reduction of health inequalities at both national and system level.

The approach defines a target population cohort – the ‘Core20PLUS’ – and identifies ‘5’ focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement.

More information can be found in the supporting document.

PLUS population groups may include:

- Ethnic minority communities

- Inclusion health groups

- People with multi-morbidities

- Protected characteristic groups

- Inclusion health groups which include:

- people experiencing homelessness

- drug and alcohol dependence

- vulnerable migrants

- Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities

- sex workers

- people in contact with the justice system

- victims of modern slavery

- other socially excluded groups.

- Population health is an approach aimed at improving the overall health of an entire population. There is no universally accepted definition, but it is closely linked to health inequalities and addressing the social determinants of health

- The Long Term Plan sets out new commitments for action to improve prevention

- New Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) will help deliver this as the NHS moves from reactive care towards a more preventative proactive approach

- The King’s Fund has a 4-pillar framework for population health which includes action to reduce ill health, deliver integrated health and care services, work with community and partner agencies and address the wider determinants of health

- The King’s Fund has also produced an animation and written several documents below, focusing on population health, including the vision for population health and what improvement looks like:

- The Network Contract DES recommends that a “PCN must work in partnership with commissioners, social prescribing schemes, Local Authorities and voluntary sector leaders to create a shared plan for social prescribing which must include how the organisations will build on existing schemes and work collaboratively to recruit additional social prescribing link workers to embed one in every PCN and direct referrals to the voluntary sector.”

- The Network Contract DES introduced a new personalised care service specification for 22/23 for proactive social prescribing earlier this year which places a greater emphasis on partnership working: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/directed-enhanced-service-personalised-care-March-2022.pdf

- This supports the Tackling Neighbourhood Inequalities service specification, as well as ICS integration and population health approaches

- Key points include:

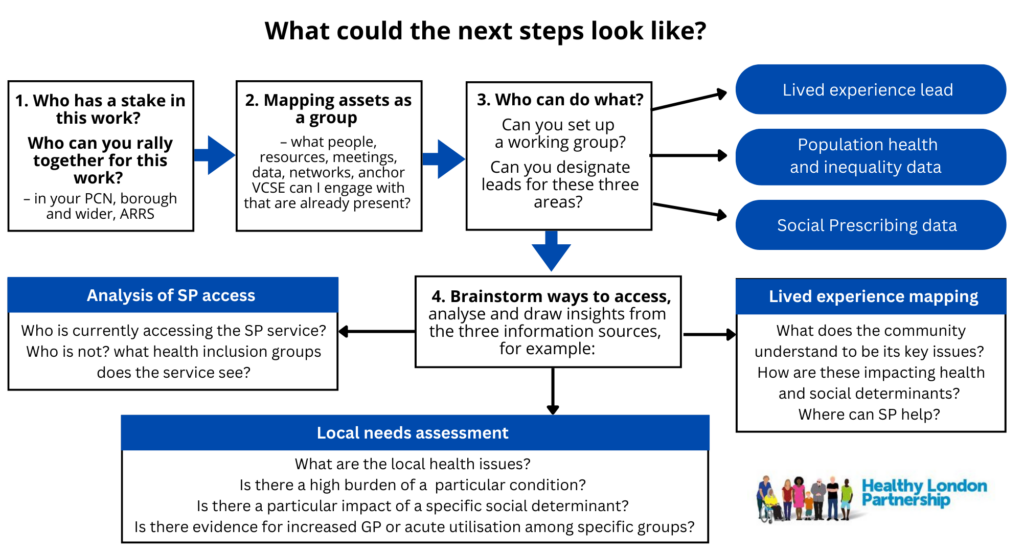

– By 30 September 2022, as part of a broader social prescribing service, a PCN and commissioner must jointly work with stakeholders including local authority commissioners, VCSE partners and local clinical leaders, to design, agree and put in place a targeted programme to proactively offer and improve access to social prescribing to an identified cohort with unmet needs. This plan must take into account views of people with lived experience.

– From 1 October 2022, commence delivery of the proactive social prescribing service for the identified cohort.

– By 31 March 2023 review cohort definition and extend the offer of proactive social prescribing based on an assessment of the population health needs and PCN capacity - Proactive social prescribing builds on the Tackling Neighbourhood Health Inequalities (TNHI) service specification which recommends that a PCN must identify a population within the PCN experiencing inequality in health provision and/or outcomes and develop a plan to tackle their needs

- It also aligns with the “PLUS” component of the national CORE20PLUS approach.

When identifying needs, it is important to consider a mix of data sources and approaches.

a. Using Quality Improvement Methods to identify cohorts for proactive social prescribing:

- Strengths-based approach

- Identify exemplars in the local community and learn from what is working and how that can be applied.

- Build from strength e.g. pre-existing relationships and networks.

- Learn from the voluntary sector what works close to communities.

- Co-Production

- Engaging communities in design, implementation & evaluation – ensure this is adequately resourced and invested in.

- Genuinely listen with curiosity.

- Engagement community engagement leads.

- Data-driven Improvement –Cycles actionable insights, generated from data, which drive improvement to interventions leading to intelligence about what works.

- Population health management overlaps with but is distinct from population health.

- Population health management is a data-driven methodology to identify and target specific cohorts of a population for predictive prevention, which supports proactive social prescribing.

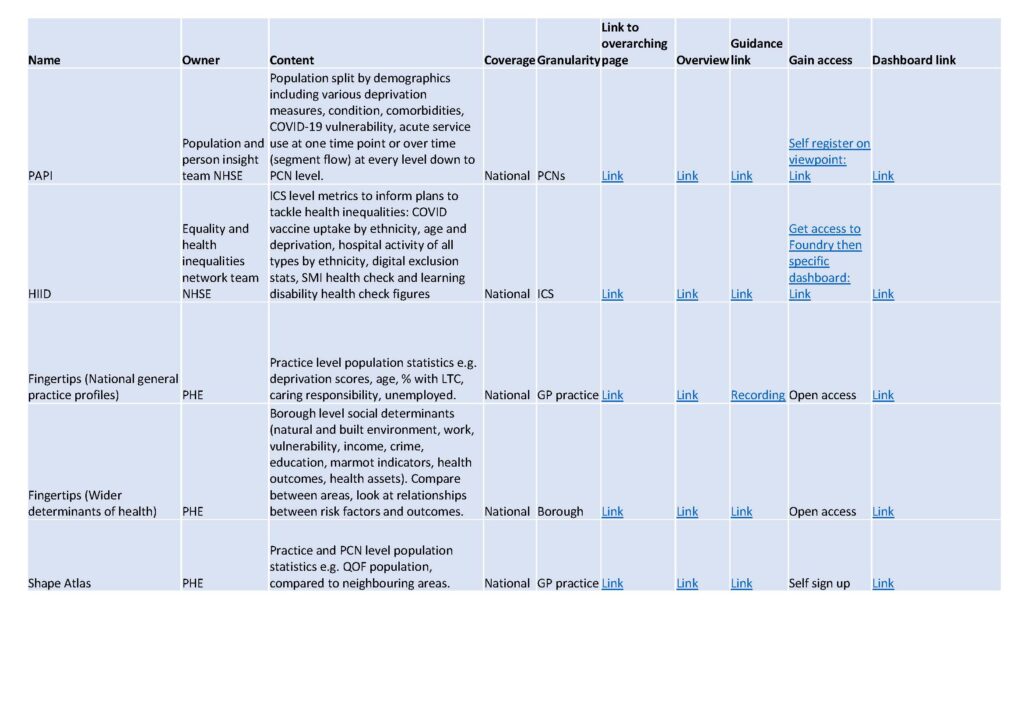

b. Quantitative data sources

- Public Health teams in local authorities, and analytical teams in ICSs, can supply further intelligence to inform the selection of the population – especially via the fingertips tools.

- The Health Inequalities Improvement Dashboard (HIID) brings together a range of indicators to help users, from national to local level, understand where health inequalities exist in their area; what is driving these inequalities; and what local insights and actions they can take to drive improvement

- Priority Wards (contained within EHI RightCare Packs) will be added to the dashboard which will include quarterly data identifying Priority Wards together with the top 10 conditions for each ward and place

- The ‘Core20’ and ‘PLUS’ target population components of the Core20PLUS5 approach should guide PCNs in population identification.

See table below

c. Qualitative data sources

Qualitative data sources are particularly important for proactive social prescribing to identify unmet need and insights on lived experiences and build community intelligence. This requires:

- Strong partnership working with community groups and leaders.

Building trusting relations and connections - Continuity and joined up working with community forums and MDTs across agencies

- Listen to practice staff; receptionists and the administration team dealing with A&E and 111 letters will know about high intensity service users requiring increased support.

To find out more proactive social prescribing you can watch back our webinar here.

The webinar includes a case study showing how a foodbank in one PCN identified health needs and brought together key stakeholders to target multiple aspects of health inequality, including SPLWs sitting in food banks and outreach health workers.

You can also read our case study on Richmond where pockets of health inequality in an affluent borough were identified, and a collaborative community outreach plan developed. Other health inequalities case studies can be found here.

To deliver the Proactive Social Prescribing aspects of the requirements, PCNs may wish to:

- Ensure there is a proactive social prescribing strategy and form a local outreach team for each PCN to work collaboratively with local partners to co-produce and inform service design for accessible and sustainable provision for the patient cohort(s).

- Use multiple data sources; quantitative data and dashboards in conjunction with intelligence from social prescribing services, voluntary sector organisations and lived experience to identify the patient cohort(s)

- Set targets for improved access and monitor performance against these; for example, reviewing targets and outcome measures

- Increase service capacity where available, using funding from the ARRS scheme where available; including, if possible, recruiting specialist Social Prescribing Link Workers with specific skills or knowledge for the patient cohort(s) identified. Additional sources of funding from the PCN development fund, HI funded pots and co-commissioning models can be explored as well as linking to existing targets e.g. QOF or GP burden

- Implement the national social prescribing minimum dataset, including demographic data collection, when introduced in 22/23.

Health inequalities

The Equality and Health Inequalities Hub

King’s Fund guide for more information

Reducing health inequalities in your local area: a toolkit for clinicians

Resource Box: Training and support for Health inequalities

Curriculum to support primary care teams to tackle health inequalities

Health Education: Inclusion Health Education Mapping and Review Full Report

UCL Health and Society Summer School: Social Determinants of Health

The Royal College of GPs Health Inequalities learning hub

The Royal College of Physicians e-learning course: Introduction to the social determinants of health

RCGP NWL Deep End support group: email Nicola.husbands2@rcgp.org

This section of the website represents the historical record of a legacy programme which is no longer managed by TPHC, as of mid 2025.