Evaluation of the Lived Experience Practitioner Programme at the Healthy London Partnership

Introduction

In March 2021, the Healthy London Partnership commissioned Peer Hub CIC to evaluate their LXP Programme. This report outlines the findings of that evaluation. This report is a business intelligence report: we provide our best answer to the evaluation questions, and focus our attention on recommendations for action and our evidence based rationale.

For the purposes of this report, LXP or ‘Lived Experience Practitioner’ refers to roles where individuals are recruited due to having personal, first person experience that is relevant to their role (such as being a mental health service user) and are expected to use that experience as a knowledge and skill base to inform their work.

We found that the LXP programme has had some real successes, and there is a huge amount of potential to build on and deliver transformational change by embracing the expertise of lived experience. However, the programme suffers the flaws of national involvement policy and institutionalised injustices. These problems

can only be resolved through collaborative working with LXPs and thinking beyond the LXP programme to how the Mental Health Transformation Team works as a whole. How can the LXPs help the Mental Health Transformation Team improve their outcomes in business as usual – not just as an adjunctive addition that is invited into certain spaces and projects?

Many business organisations would be thrilled to have the wealth and depth of ‘consumer’ expertise the Healthy London Partnership has available to help guide their strategic decision making. It’s now up to the leadership – in collaboration/negotiation with LXPs – to map their route forward, formulate good practice into policy, and determine whether what exists now is ‘good enough’, or whether there is an ambition to take their LXP programme to the next level.

A note to participants

Thank you to everyone – LXPs and staff – who took the time to contribute to this evaluation. Whether you took part in the survey, interviews or focus group, or helped shape the evaluation through the steering group and meetings; your contributions have been vital to us being able to produce this evaluation.

As you read through this report, we hope you are able to see your contributions and how we have drawn from what you have told us collectively to inform our overarching findings. We hope you find our report helpful and interesting, and wish you all the best of luck for the future of your work together.

How to navigate this report

There are two main sections of the report:

In the first section, we give our best answers to the questions you asked us to address in your evaluation framework.

In the second section, we lay out our evidence and our thinking, and we ask ‘so what?’ – that is, what does this mean? Why is this important? And then we make recommendations to strengthen the LXP programme based on the things you told us were important both in the evaluation framework and across the evaluation itself: in the interviews, focus groups and surveys. This section starts with an executive summary that provides an overview of our findings.

The second section is broken down into two overarching themes: in Part One we explain the structural and policy

weaknesses of the programme, and offer recommendations on how these could be changed to free the programme up from its current limitations. In Part Two, we explain the inconsistencies in the current programme and what we think is possible within the limits of its current structure and policy.

The recommendations in Part Two are designed to improve on what already exists, without requiring structural change.

Section One: Your Questions

In this section of the report, we answer the questions you asked us in your evaluation framework.

The full evaluation framework is available at Appendix I.

The framework provides the overview of the five questions you asked, and the themes you asked us to

explore.

Inclusivity and Health Inequalities

To what extent are the programmes inclusive and contributing to address health inequalities?

Inclusivity: we asked both staff and LXPs whether the right people were involved in the LXP programme.

There were mixed results. While there is diversity in the LXP programme, this could be improved.

The critical issues are whether the expertise and knowledge from diverse communities is able to

influence the work of the HLP; and also, whether LXPs are able to collectively advocate for the

interests of excluded or oppressed groups. At the moment we would say neither of these is happening

consistently, though there have been good examples.

We think changes need to be made to the LXP programme and where/how LXPs contribute to the

HLP workstreams to share the burden of anti-racism, anti-ableism and other social justice work. The BIPOC

LXPs in the existing programme would be well positioned to help HLP explore matters relating to race

and BIPOC experiences. They should have effective support to do this, due to the burden anti-racism work places on BIPOC people.

Health Inequalities: the links between the work the Health London Partnership Mental Health Transformation Team does and its ambition to reduce health inequalities are unclear, including in the LXP programme.

While it can be seen from examples like the Podcasts that there has been work done to raise the voices of black and brown people, for example, it is unclear from a programme perspective how this tracks back to a strategic effort to create meaningful change in relation to health inequalities in communities.

It’s clear from what staff and LXPs have told us that there is a real drive to tackle health inequalities. However, there is no meaningful structure or strategy for how they will do this, or clear framework for how lived experience knowledge can help. The programme workstreams are not set up in a way that centres health inequality as a theme, or with a consistent place for these important issues to be tackled or monitored. Nor are there any measures or metrics that can meaningfully assess the outputs of the relevant programmes.

In Part One, we recommend ways this could be improved, by investing some time and resource in identifying strategic priorities that offer more clarity: both programme-wide and for the LXP group.

Principles of Co-production

To what extent is the work of the programmes aligned to the principles of co-production?

The qualitative element of the evaluation considered the programme against the 4Pi framework and found that most LXPs felt respected and valued in this process. Alison Faulkner’s report is available at Appendix III and gives a fuller answer to this question on terms of LXP experience.

There is evidence of co-production being done well in some examples, and also some areas where it isn’t being done very well. We have considered this question more thoroughly in the business intelligence sections of this report, which looks at how lived experience knowledge is used and where the programme can address power imbalances. This evaluation is a good opportunity to reduce inconsistency and learn from examples where coproduction is working well, such as:

- Access Statement

- Eating Disorders Pathways

- Digital IAPT E-Triage

- Podcasts

The qualitative review found that there are some things the programme can do to improve experiences of co-production, including:

- Retain the value and respect felt by most LXPs by the programme team

- More space for support and supervision: reflective spaces

- Consistent policies and procedures: e.g. for payments, work allocation

- Training – particularly for sharing personal experience and keeping safe

- Greater transparency and clarity in general about the purpose of meetings and workstreams, policies & procedures

- Consistent communications throughout, including about meetings

- Regular attention to feedback and evidence of impact

- Space for LXPs to meet together and build a sense of solidarity, ensuring that this is an inclusive and respectful space for BIPOC LXPs

The main body of this report outlines suggested actions to deliver these recommendations.

Influencing Wider Involvement

How can the work of the MH Transformation Team influence wider LXP involvement in HLP and externally?

At the moment, the most influential elements of your LXP involvement programme are the stories and case studies you are building to show what happens differently when lived experience knowledge is part of project work. Examples like the podcasts, which were widely reported as good experiences, and the work on digital IAPT e-triage are good news stories that you can share.

It’s important to remember, however, that there is also learning in these projects. Not every LXP had a good

experience in these good practice projects. It’s important to capture the knowledge of how you respond to these negative or critical experiences. Involvement programmes nationally have inherent problems based on their structural design. There is lots of interest in what doesn’t work well and how these problems are solved, that your programme can lean into to sell the good work you are doing.

It’s a good idea to make it easy for people to come to you if they want to learn how to do involvement

well. And also, to share what doesn’t work, and how LXPs help solve these problems, rather than being the

subject of them.

The best ways of influencing positive change are Hospital relational, including sharing stories of good experiences. There are two main things that it is important to share:

- Personal stories of involvement when it has felt good, and what that meant for the quality of the

work. - How involvement is helping to solve problems and ways you are experimenting with involvement in

your approach.

This draws from the Diffusion of Innovation approach which suggests that at this stage in the development of your programme, it’s people’s personal interests, relationships and aspirations that count. According the Diffusion of Innovation model, there will come a time when you will need to use benefits and evidenced outcomes to be able to influence wider proportions of leadership and staff groups towards co-production. To prepare for that future, you could take time now to look at what you need to measure and how you demonstrate the benefits of your programme. We suggest some ideas for things you could try to measure to show your good work at Finding 6 (feedback and impact).

In the meantime, keep talking about the good work you’re doing! And, keep trying to build evidence of good practice in your day to day work.

Policies and Procedures

Are the process, policies, and procedures in line with the overall ambitions of the programme?

Much of the content of this report relates to policy and process. The best way to summarise our view on this is that the people and their commitment hold the programme together and are struggling to realise its potential within the limitation of existing policy. They need a little more help from better structure, strategy, policies and procedures.

We would recommend that the Mental Health Transformation Team’s strategy and processes be reviewed now that the people involved in those processes includes LXPs. LXPs offer a critical element of business information and knowledge that is largely missing from the staff team and programme information and data inputs. They also have different skills, expectations and needs to the existing staff group. It should also be noted that our survey suggests the programme hasn’t always done well to take into account their individual needs – in particular, any reasonable adjustments under the Equalities Act 2010. This is a policy/process problem, rather than an intentional omission.

Our evaluation suggests that much of the gaps in policy and process is because there aren’t any staff roles specifically to manage the LXP programme. Programme managers do not have the time to do the work need to formalise good practice into policy and process. As it currently functions, the HLP does not have the time or resource to run this to its full potential. There is the possibility to take what is working well — the previously unknown issues that LXPs have shone a light on, the projects they have saved from failure due to their insights and expertise, and their unique position to truly point the work of the programmes at the places in communities whose struggles are unseen — and make this business as usual, to improve the HLPs impact and performance. Policy and structure is needed to do this well, and that policy and structure should rightly be designed in collaboration with LXPs based on the learning from this introductory phase.

We think the LXP programme is critical to good business operations for the HLP and is worth formalising as a programme of work, with associated staffing in the Mental Health Transformation Team. The pilot LXP programme would flourish if it could be better integrated as a core element of business strategy, process and decision making. The LXPs have a wealth and breadth of knowledge and experience that the Healthy London Partnership doesn’t always know it needs, but that will prevent projects from failing, running off track or aiming in the wrong direction. It is policy, procedure and process that are preventing this from being realised at the moment, not the capability of your staff team or your LXP group.

Impact of Covid-19

What have been the challenges, impact, and opportunities in relation to Covid and new ways of working?

During our negotiations on how to conduct this evaluation, we agreed that this question would not be a primary focus so that we could provide a more thorough evaluation in other areas. We agreed to report on incidental information relating to Covid-19 and new ways of working that came up during the course of the evaluation. We will therefore only be able to partially answer this question.

The LXP programme started during the Covid-19 pandemic, so there is no before/after to compare in terms of the impact on staff/LXPs. Some LXPs said that the online, remote nature of the programme allowed them to participate in ways that would not have been possible if the work was in person for various reasons – prohibitive travel times/routes to meetings, the limitations on time of other personal/work commitments and health/disability related barriers were the most commonly cited.

The remote nature of the work, however, has also contributed to feelings of separateness and isolation among the LXP group. Many LXPs have expressed an interest in in-person meetings or opportunities. This is likely to reduce feelings of isolation and increase the potential for teamwork for those who want to and are able to attend.

Noting the barriers to in-person work for a number of the LXPs, it is vitally important that any in-person gatherings are conscious of the barriers for LXPs who would struggle to attend. Accessibility for people should be a key consideration for any intentions to move to a hybrid remote/in person approach.

For full LXP group meetings, we would suggest that LXPs who face the barriers we have outlined are key members of any team who are organising any event, and enough planning time and budget is in place to ensure accessibility for all is possible.

Section Two: Our Findings

In this section of the report, we show you our findings and report on the evidence we used to build them. We also outline our recommendations for next steps.

This section of the report highlights data and information that we collected during the evaluation to demonstrate our findings. Our information sources are available in the appendices.

Executive Summary and Overarching Findings

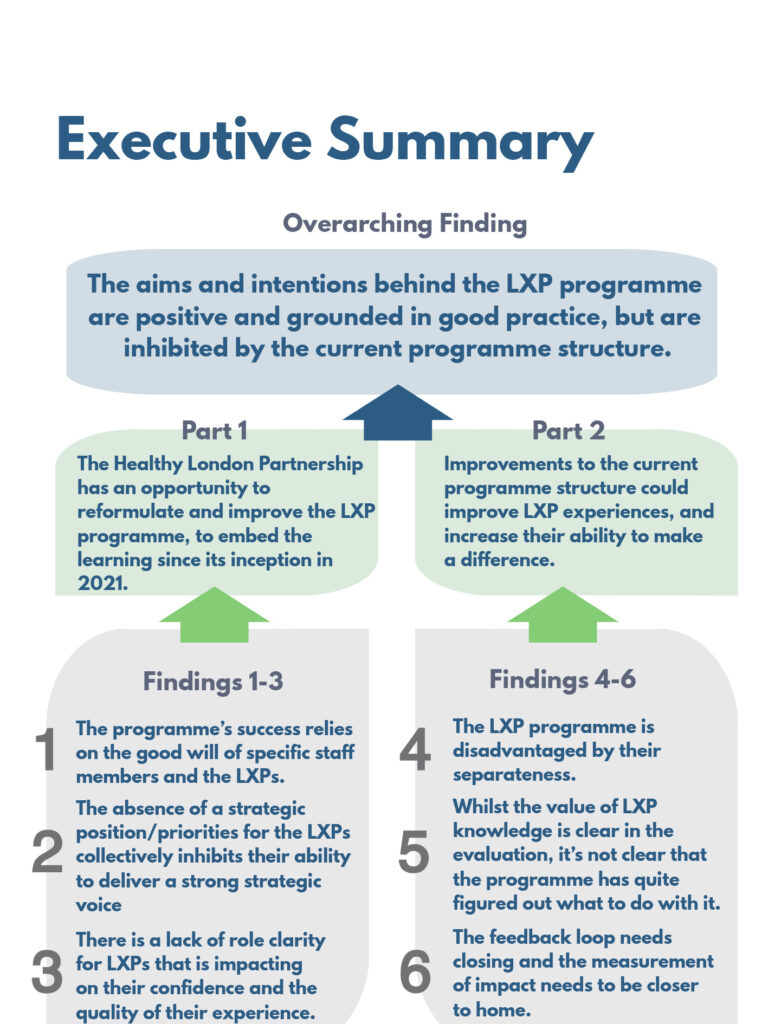

The aims and intentions behind the LXP programme are positive and grounded in good practice, but are inhibited by the current programme structure.

The LXP programme is based on national good practice and has built upon that successfully. However, it also has the ingrained flaws of much of the national best practice, in that involvees remain stuck in patient/service and institution/ community dynamics. Thus, it inadvertently replicates many of the issues inherent in those systems for community members and service users; including institutionalised racism, ableism and sanism. Elements of the HLP programme have worked very well in its current format. Formalising good practice in policy would go a long way to helping the programme consistently deliver good practice.

There are limited resources available to manage the programme, and further limitations to potential in the current programme structure. For as long as the current format remains, the programme will sometimes fall short of co-production or collaboration, and sometimes excel. Also, some LXPs will feel exploited or undervalued, and others will feel very valued and very respected.

Part One of this report looks at what is possible if the HLP is willing to make strategic change to its ways of working, by applying the lessons from the programme to integrate LXP knowledge into business as usual in the Healthy London Partnership. In Part Two, we have suggested ways of formalising the things that have worked well in the current programme format. Part Two will mitigate some of the embedded issues in the current structure, but is unlikely to resolve them entirely.

Part One: Reformulate and Restructure

The Healthy London Partnership has an opportunity to reformulate and improve the LXP programme, to embed the learning since its inception in 2021.

Implementation Significance

Strategic Development – Structural Change

Implementation Strategy

- Development of an LXP Strategy and formalised LXP programme workstream.

- Co-produced review of Mental Health Transformation Strategic Priorities and project delivery approach.

- Development of role profiles for LXPs in different strategic and operational provisions, to make the most of the skillsets of LXPs.

Executive Summary

The evaluation findings have been separated into two parts. Part One

considers the overarching structure of the programme and what could be

possible if there was an appetite for strategic change to the way the

programme is being delivered.

In this section we consider how the LXP programme interacts with business as usual in the HLP,

to support the long term aims of the Mental Health Transformation Team, and how current

infrastructure helps or hinders these aims.

One of our key findings in the evaluation was that the LXP programme relied heavily on the

good will and knowledge of staff in the Healthy London Partnership Team, rather than on

processes, policies or procedures that support good co-production. We found that the

programme is technically invisible in the HLP structures, making it vulnerable and absent from

organisational knowledge. Many LXPs have reported to us that they struggle to see the impact

of their work. Some suggested that they would like to see a more concerted effort to use

more structured methods to approaching problem solving and delivering on objectives. There

is a lack of strategic direction for the group, and as a result of the general uncertainty in the

programme, there isn’t much role clarity for the LXPs.

The role profiles and the expectations of the LXP programme were quite open and undefined as

the programme began. However, we now know much more about what is working, and not

working, and where LXPs are helpful and how – both positive and critical – since the

programme started in 2021. How Lived Experience knowledge is needed in the programme is

clearer, and where there are strategic gaps is easier to identify. The the roles of LXPs and the

LXP programme can now be more clearly updated and defined. It is easier to see what the

Mental Health Transformation Team need from LXPs, what LXPs can offer and where the

LXP programme can be better integrated with business as usual to maximise the skills and

expertise of its members.

Our recommendation is to move from the ‘pilot’/introductory phase into building the LXP

programme into business as usual as a core part of the transformation team. This means,

looking across the whole business model for the Healthy London Partnership at where LXP

skills and expertise are needed and can have the most impact. We recommend this as a long

term programme of work, starting with developing a joint strategy and action plan with clear

strategic priorities. The LXPs can then be tasked with more focussed roles that maximise their

impact.

Finding 1: Relying on Goodwill

The programme’s success relies on the good will of specific staff members and the LXPs. This leaves the programme vulnerable to changes in personnel or disengagement from the group.

What LXPs told us…

The positive experiences of LXPs that were shared in the interviews and focus groups, and how

much this relies on the relationship with the programme team, are outlined in detail in Alison

Faulkner’s qualitative report at Appendix III.

“That consistency of her unrelenting positive regard for us sets a strong tone for the team or in meetings and wish I saw it more in the field. The importance of this attitude cannot be underestimated and really is a foundation of any involvement or coproduction work. We need to take this beyond a few individuals leading by example to an established standard for coproduction.”

(LXP: survey respondent, about a member of the programme team)

The LXPs have told us about their dedication to the programme, and how much the support of

the programme team helps them stay involved. This is despite a number of issues with the

programme, not least the significant problems LXPs have encountered with payment processes.

“I do it because I feel respected,

valued, appreciated. And because I like the team. And that’s for me, it’s that simple, really.”

(LXP: interviewee)

“They’re just really caring and

supportive and listening and they

don’t kind of dismiss what you have to say. And that’s very important.”

(LXP: interviewee)

“The incredible lack of dropout/retention!”

(LXP: survey respondent)

We found in interviews, focus groups and the LXP survey that the relationship with the programme team

is very important. Where LXPs have had less positive experiences, disconnection with the programme

team has been something that has been cited as an issue.

The LXPs have continued to work with the programme despite the issues they have encountered. Most LXPs reported feeling valued and respected, and this has been an important factor in maintaining LXP involvement when elements of the programme haven’t worked very well.

“The LXP role is more than a job – it’s not easy to be vulnerable, share lived experience and manage your own health alongside your desire to help others and the payments are far from demonstrating that value either.”

(LXP: interviewee)

“The flip side of that is like, if I was working on a contract basis as part of the IT supplier, I’d be getting paid a great rate to be doing [this work].”

(LXP: interviewee)

Feeling valued by the team and their relationship to other LXPs are the things that shine through in

the positive feedback we have received. Despite the number of barriers or struggles that they have

encountered in the programme, or where the programme that has not met their expectations, most

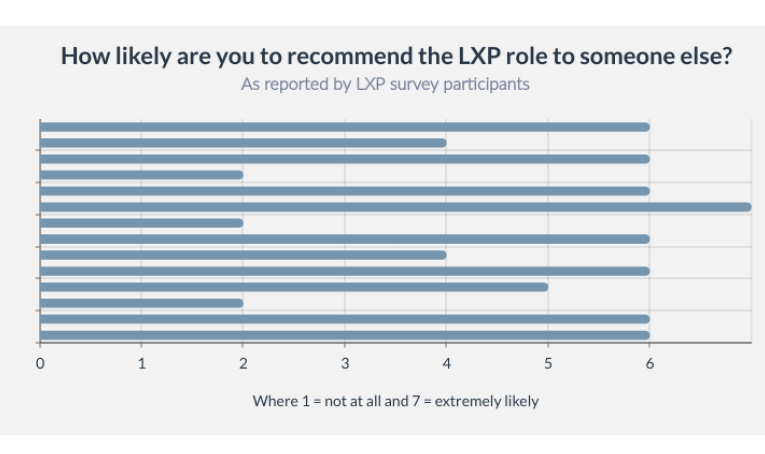

LXPs would recommend the programme to others (9 of 14 survey respondents*).

*3 respondents were unlikely to recommend the programme to others, 2 would neither recommend or not

recommend, and 9 were likely to recommend or highly likely to recommend the programme to others. There were

different experiences within the cohort which may have led to the lower scores for this question. Despite issues with

payments featuring highly in the survey due to its timing, it could not be said if a better payment process would have

changed this outcome and this should not be relied on as the main driver for the answers to this question.

What staff told us…

Programme team staff shared their commitment to the LXP programme with us, including how much they valued the work of the LXPs and also their relationship with them. The staff team have huge ambitions for the LXP programme, and there is a real sense of possibility of what could be achieved if the programme was able to meet its potential.

“It would be great to have the LXP involved in more of our governance structures.”

(Staff: Survey respondent)

“I feel like we’ve got a post missing.”

(Staff: Interviewee)

“Their input is essential. Their exclusion in the past meant

initiatives failed.”

(Staff: Survey respondent)

There are lots of real positives in the LXP programme. The elements that work well, however, require staff time and resource. LXPs report into the Healthy London Partnership individually so managing their needs, complaints or concerns is a big draw on staff time and resource. Each programme manager has taken on the role of supervising a team of LXPs in order to facilitate co-production in the workstreams, including supporting their individual needs for accessibility and support. This is in addition to their existing workload, and not a planned component of their role. This unintended consequence of the programme is unsustainable in the long term.

However, it is only the fact that Healthy London Partnership team members are willing to do this extra work that the programme is working as well as it is. The reason staff are willing to do this work is because of the outputs they are seeing and its impact on the programme. It is also likely that the inconsistent experiences of LXPs are due, at least in part, to this limitation on resource and time, and a lack of ability for programme staff to reliably place LXP support/supervision as a priority in their workload. While everyone is trying their best and working with what they’ve got, essentially what gets done and when is largely dependent on the programme managers finding the time, rather than the needed resources being accounted for and ringfenced in funding and policy as part of business as usual.

Business intelligence

Business intelligence tells us a lot about the vulnerability of the LXP programme. Despite the good experiences and good faith between LXPs and programme team members, from a business intelligence perspective, the LXP programme is very vulnerable. Changes in key personnel could seriously destabilise the programme. The programme relies on the good faith efforts of staff and LXPs to continue working despite the inherent barriers in relation to investment, disempowerment and systemic inequality.

Programme Invisibility

It’s understandable that the programme would be experimental and ad-hoc during its ‘pilot’ phase, as the Mental Health Transformation Team and the LXPs figure out how it is going to work. What this means, however, is that the programme is running ‘between the lines’, in the time the programme managers can find in between their contracted duties. The good practice that is emerging in these conditions should be built on and formalised – such as the development of the Access Standards, the Digital IAPT E-Triage, the development of the podcasts and so on (noting that there will also be learning points and weaknesses in each of these projects).

However, the problems with running a ‘between the lines’ programme and workforce came to light in the last 12 months. Despite the efforts of staff to ensure the LXPs weren’t left behind in the transfer between host organisations in July 2021, the LXP programme was invisible in organisational knowledge for the purposes of that transfer. There had been no negotiations or preparations to ensure the LXPs were treated fairly and minimally impacted by the transfer. The LXPs had little protection from the disruption of the move – without the status of staff, contractors or other ‘suppliers’ who will have contracted protections against losses during such organisational change processes. There are inherent risks to the organisation, programme staff and the LXPs in not formally recognising a workforce (LXPs) who are, in effect if not on paper, providing labour and/or services to the organisation.

Working terms and conditions

When LXPs talk about exploitation or discrimination, part of this is because their skills and expertise are all being pitched at the lowest common denominator: that is, their status as psychiatric/mental health patients. Involvement payments are not designed to be used as a means by which to pay for anything other than ‘patient involvement’ (see Appendix VII). Nationally, many NHS involvement programmes have been carefully established to allow maximum flexibility for the host organisation with minimal liability for involvees. They have been developed on a ‘market research’ type basis, where involvees contribute to patient reference groups in the same way that customers contribute to customer focus groups in market research programmes. The HLP programme is bound to this model by national policy.

However, the HLP role profiles for LXPs tell us that their role has greatly expanded beyond patient involvement, and the expectations of lived experience contributions in involvement programmes now is much more akin to consultancy services. This has placed involvees/LXPs in unstable ‘non-working’ roles whilst treating them as a working’ resource in many ways, and holding them in patient involvement policies and processes. Meanwhile, the skills, abilities and expertise that are being requested in the HLP programme go beyond ‘patient experience’ type contributions. This is a national issue for involvement programmes and the Healthy London Partnership is in a good position to review this with the LXPs now that the programme has been evaluated. What is the best outcome for LXPs and the HLP if their work is considered in context, and options outside involvement processes are considered? Or is the involvement structure still the best option, even with its inherent flaws?

Payment, value and parity

The amount of payment is also a recurring theme in contributions to the evaluation. Payment for LXPs was based on a set rate of £150 per day or £75 for up to 4 ours of work. However, this is a patient involvement rate, and perhaps as much of a tenth of the day rate that a lived experience practitioner working at a strategic level across London could expect to be paid. The parity between what is being asked for and what is being paid for could be viewed as quite different for much of the expertise that LXPs are expected to bring.

The LXP programme has to be affordable, but the programme is at risk of exploiting the willingness of LXPs to work at reduced rates to achieve their personal goals of seeing change in NHS services. The Healthy London Partnership should also note that salaries for employed LXPs also take into account the preferential terms and conditions of status as employees. At the moment, the LXPs are expected to be a resource that the HLP can access like an employed workforce, without any of the safeguards or benefits that employees enjoy rates of pay that have been negotiated against market standards – rather than against patient involvement national best practice. The positioning of the LXP programme in involvement structures is both problematic and offers flexibility and opportunities. The question for the Healthy London Partnership and the LXP cohort is whether this is something that ought to continue as it is, or whether there needs be a rethink on the terms of the relationships between the HLP and (all or some) LXPs.

Case Study: Payment Problems

Payment was a very hot topic during the time the evaluation was being undertaken. There were

some months of disrupted payments in the first half of 2021. Then, in July 2021, the transfer of the

Healthy London Partnership to a new host organisation and a complete change in payment policy

delayed their payments further. The payment process needed to be completely reviewed, since the

new host organisation did not have an involvement payment process in place.

What LXPs said…comments from interviews

and surveys.

“But if the staff weren’t getting paid, all hell would

break loose.”

“I need to get paid because I need to pay my bills. And

I worry a lot about money.”

“Payment systems…puts all responsibility on LXPs to

organise their own tax arrangements, as if we are

‘self employed’ contractors.”

“Payment process I am still waiting to be paid since

February 2022 …Nothing offered in the interim other

than we can have the option to stop the LXP work

until we are paid.”

“Often asking for additional tasks without offering

pay.”

“Our role was framed as being peers and colleagues

to clinicians and other staff members. And yet issues

like non-payment…make it clear that we’re not.”

The protection of good

will…

Despite all of this, we did not hear reports of any attempt to enforce payment collection, or any concerted efforts from the LXPs to enter into collective action. The good will between staff and LXPs may not just be the grounds for good work, but may also be the reason that there has been no organised challenge to the format of the programme by LXPs.

Graph to be added

So what?

As the programme currently stands, it is working very well for most LXPs, but not so well for

others. Much of the reason why LXPs stay involved is because of their relationship to the staff

team and their commitment to making a difference. The good will of the staff team, and how

much they value lived experience expertise, is the reason why the staff team have gone above

and beyond in their own roles to make this programme a functioning reality.

Although there is much to be said for the goodwill between staff and LXPs, there is an

undercurrent of resentment around exploitation and harm for some members. The LXP

programme relies on people who are committed and connected leaning into staff

relationships. It is also based on a national model where involvees have no legal rights, may not

have the financial security challenge their working terms or are otherwise disempowered to raise

a challenge without negative consequences to themselves. We do not believe that this is an

intentional position on the part of the Healthy London Partnership, but it has been something that

has been made apparent by some contributors, particularly in the survey. It is an unintended

consequence of aiming for flexibility over formality.

The Healthy London Partnership would lose a very powerful source of information, business

intelligence, skill and capability if the LXP programme collapsed because there was a change in

personnel or a disengagement of LXPs due to the format of the programme. Now is a good time

to formalise good practice into policy, and collaborate with LXPs to ensure the design of the

programme fills some of the gaps identified in this report, solves some of the problems and

reduces the potential for harm and exploitation. This will be a challenge in terms of ensuring

that the programme is accessible to a wide and diverse range of LXPs, which is why LXP’s

co-producing policy and formalisation is critical to it not excluding communities that are essential

for the success of the programmes of work.

Recommendations

We recommend formalising the LXP programme through a programme workstream in the Healthy

London Partnership, with at least one lived experience programme manager and a co-produced

programme action plan. The programme of work should seek to action the outcomes of this

evaluation – whatever the Healthy London Partnership and LXPs choose to do. This includes

whether the HLP decides to accept our recommendations, or decide on a different route forward.

We would hope to see a formal LXP programme emerge, with a hope that in time the work

that the staff and LXPs do well can be integrated as business as usual in the Mental Health

Transformation Team.

Finding 2: Strategic Vision and Priorities

The absence of a strategic position/priorities for the LXPs collectively inhibits their ability to deliver a strong strategic voice from their combined perspectives and diverse individual attributes.

What LXPs told us…

“I am a little bit like, where’s all of this going?”

(LXP: interviewee)

“Think it’s clear until I become more involved and the complexity makes it less clear.”

(LXP focus group 1)

“Who’s doing what? Why am I here? What is the purpose?” (LXP focus group 2)

A common theme in contributions from LXPs is that they are unsure what is expected of them and what their contributions are expected to achieve. There are two key elements of this: one is that the Healthy London Partnership is setting the expectations, and the second is that there is some confusion among LXPs about what the Healthy London Partnership is trying to achieve.

LXPs are sitting in submissive and disempowered roles, and that means they are subject to the programmes’ weaknesses rather than using their skills and expertise to help the programme become stronger. In a well functioning programme, the LXPs would be able to identify and help solve problems in the way the programme functions, as well as contribute to the outputs of the programme.

“I’ve never been entirely

clear on what…we’re

trying to achieve, and how

we’re going to achieve it.”

(LXP: interviewee)

“Where we’ve ended up in the sort of similar

discussions, it’s not been about a lack of

effort, it’s been about a lack of clarity or

confusion about what to do.”

(LXP: interviewee)

“Meetings need clear brief – outline what do we want

to achieve at the outset of meeting, evaluate at the

end if we’ve met the original aim(s) and identify next

steps (who, what, when)..”

(LXP: survey respondent)

LXPs noted that there was a lack of structure to the process that enabled the programme to be impactive; things are loose around having a purpose, method and intended outcome. A number of LXPs also have knowledge of what good problem solving process and project planning looks and feels like. If better services for service users and reducing health inequalities are among the aims of the programme, then LXP expertise is vital to identifying the problems that need to be solved and where good data sources are for finding out more about those problems.

“I actually think that time would be better spent

talking as a group about where the issues are in

services and what we want to change, setting some

goals, and then working towards those changes.”

(LXP: survey respondent)

Finding 3: Role Clarity

Part One: Summary of Recommendations

Part Two: Opportunities to Improve

Part Two: Executive Summary

Finding 4: Separateness

Finding 5: Lived Experience Expertise

Finding 6: Feedback and Impact

Part Two: Summary of Recommendations

Report Limitations

Summary Comment

Appendices

To what extent are the programmes inclusive

and contributing to address health inequalities?